Writing in the Perfumery & Essential Oil Record in 1958, Leo H. Narodny described an experiment investigating whether the scents of essential oils could induce creativity. He reminds his readers: "the smell of dried applies in a desk gave inspiration to much of Schiller's poetry. Richard Wagner found that the smell of roses and the sight of golden satin helped him to compose his operatic works."

Recent research, he observed, seemed to indicate that these aids to composition may have been more than poetic proclivities. Although "the process of inventive thinking has remained inaccessible to introspective observation," neurochemistry "has opened up a new approach to the elusive subject of creative imagination." Newly discovered chemicals such as serotonin seemed to be the material substrate of mental states. If we could only determine the chemical "causes" of imagination, he wrote, "it should be helpful to artists and writers, and perhaps guide the thinking of scientists."

And while the ingestion of psychedelic drugs granted visions — here Narodny thumbs through Aldous Huxley — these substances also seemed to sap motivation. But perhaps all you needed was to inhale. "It may be possible," he speculated, "by inhaling certain odours, to influence creative imagination without endangering the whole brain by an excessive dosage of drugs." In other words, odors could trigger physiochemical changes in the brain, and could thus produce new, unprecedented thoughts.

His willing guinea pig to test this hypothesis was the American textile designer Monica Scott. According to Narodny, her fabrics "feature distinct designs of real objects in bold earthy colors. Her style is a novel approach to reality." (In my cursory search, I wasn't able to dig up anything about her work or life, but if anyone knows anything about her, please let me know!) He describes some of her signature looks: swimsuits printed with schools of tropical fish; party dresses stamped with images of jewelry; candy-print garments for children. "What would be the effect of odors on her facile gift of creation?"

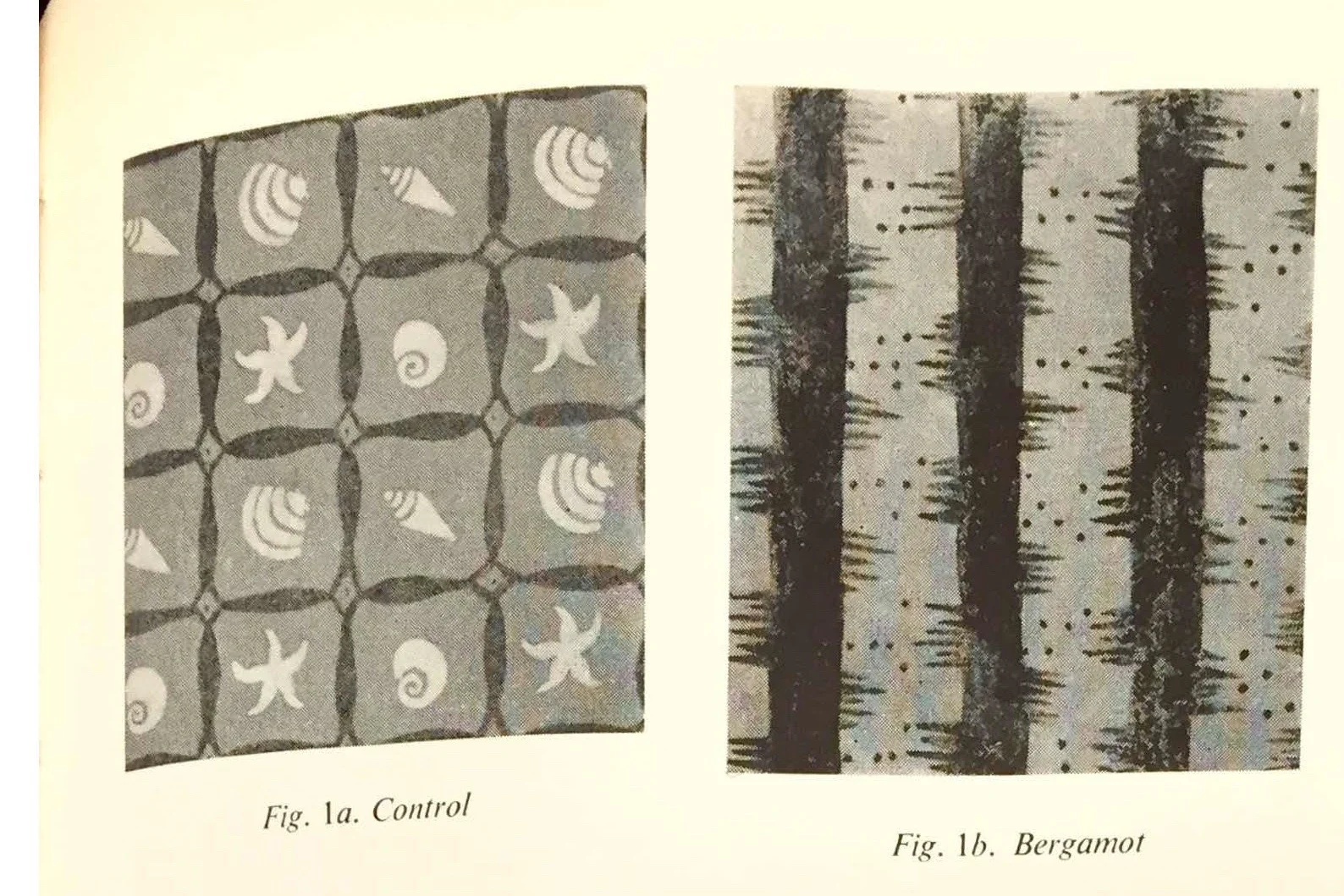

This was their methodology. For "a fortnight," Monica Scott sketched two designs each day: a control design in "normal room air" and the second made "after inhaling five litres of air saturated with the essential oil or odor under test."

This is your brain on bergamot. From Leo H. Narodny, "The Influence of Odors on Inventive Thinking," Perfumery and Essential Oil Record, February 1957.

These are the scents Scott breathes in: Bergamot; Vanilla (Mexican Prime Beans); Peppermint; (Chinese) Star Anise; Mysore Sandalwood; (French) Lavender; Bois de Rose (Brazil); Australian Eucalyptus; American Cedarwood; Arabian Olibanum (aka Frankincense); Dominica Citronella Grass; Dominican Bay and Lime Oils.

Although the sample size was too small for Narodny to properly calculate the "statistical significance of the effect of odors on inventive thinking," he did reach one conclusion with confidence. The inhalation of odors by Scott "caused a tendency to abstraction.... The symbolic response was a change from a normal 'thing' concept to an 'abstract' concept."

Bonbons become spectral parallelograms under the influence of Star Anise.

The "rounded realities" produced by ordinary air.

Compared against the "rounded realities" of the pictures produced in unscented air — "the maize kernels, the paper covered bonbons, the papi of milkweed, and the interlaced flowers" — Scott, under the influence of essential oils, tended toward "angular abstractions." Bergamot oil produced a jagged line resembling "the electroencephalographic records during sleep, or the diphasic nerve potentials of insects, the spontaneous nervous activity of the central nervous system, which occurs in bursts if measured longitudinally, and which resembles a human 'alpha' rhythm when measured laterally." Vanilla "suggested the acicular crystals of vanillin on some pods." Star Anise "an abstract series of diamonds." Peppermint the "angular designs of stars."

Acicular crystals of vanillin? The influence of chemical form on creative thought?

For her part, Scott seems to have found the experience pleasurable and useful. The odors produced changes in her mental and physical condition, arousing memories: "Bergamot had a soporific effect, and was reminiscent of the sickroom of my childhood," she testified. "With Vanilla I experienced a sense of release. I plan to use a collection of scents in my future work in fabric design."

As fantastic as these designs are, though, one can't help but feel that they are somewhat of a letdown, inevitable, perhaps, considering the gap between what was promised or hoped for (a direct through-line to the mental, material processes associated with creativity) and the more or less mundane objects of commerce produced as a result.

***

I was reminded of Narodny and his experiment with odors last month in Cambridge, at Cafe ArtScience, where I attended an event called Sensorium.

Cafe ArtScience is a restaurant, "where culinary art, science, and design meet the sustainable future of food," according to its website. Located in Kendall Square, within the long shadow of MIT, it occupies the ground floor of a new glassy building, honeycombed with its partner institution, Le Laboratoire. According to David Edwards, the mastermind of this conjugation, these spaces comprise a "cultural laboratory," a "dream environment" for art-science-design experiment, innovation, and "dialogue." Le Laboratoire Cambridge is a recent transplant to these shores, a live cutting taken from the stem of the original, which was founded by Edwards in Paris when he cashed in his chips after developing a needle-free vaccine-delivery technology.

Cafe ArtScience. Image from Slate, where you can also find a review.

Sensorium was billed as a multisensory dinner: five courses, each paired with a silent film, a scent, a cocktail. It was preceded by an intriguing lecture from Edwards, where he sketched out the history of the unusual institution and his vision for its works. I'm still trying to untangle my thoughts about Sensorium, about Le Laboratoire, and about Edwards and his project, so bear with me if and when this meanders.

Edwards is charming, with a muppety thatch of ringlets crowning his noggin and thick-framed architect-glasses. He's eloquent, but not a particularly smooth talker; he speaks almost convulsively, delivering his ideas in quanta of enthusiasm.

He is a great believer in the transformative potential of the sensory experience — olfaction in particular — to improve health and enhance human life. Like Narodny, he expresses these beliefs in terms that are more medical and scientific than metaphysical, drawing on the language of engineering and design, rather than spiritualism or self-help. All the same, the ultimate goal is transcendental. As Edwards put it, "we are starting to understand how to control sensorial experience so that we can lead better lives." By attending to sensory design, we can surpass the apparent limits of human capabilities, generate truly new experiences, enrich existence.

The following quotes are all taken from my notes from Edwards' remarks: "We control things that enter into our body" through the FDA, yet these two categories of substances (food, drugs) seem to be at the root of much of our contemporary malaise. We "overdose" on food and drugs because we are looking for a "third thing: sensation." It is in this (yet?) "unregulated" realm of "sensorial experience," he said, that new possibilities lie for the enhancement and improvement of human life.

In Paris, he had the idea of "creating sensations that are innocent," that could directly satisfy our cravings for sensation, untethered from metabolic consequences. This led to one of Le Laboratoire's signature in(ter)ventions, Le Whaf, a semi-recumbent decanter that nebulizes a liquid into a cloud that you can then sip through a specially designed straw, allowing you to sample its full flavor experience in a dose of only fifty micrograms.

Le Whaf is a peculiar instrument of knowledge, one that offers a route to food and drink connoisseurship without gourmandizing's elastic waistband. Edwards noted that Le Whaf is currently used as a tool by "expert tasters" — whiskey judges, coffee cuppers — to more efficiently evaluate the substances they are asked to assess, and also by forward-thinking chefs. (He mentioned someone, somewhere using it to produce a "cloud of sushi.")

Anticipating Le Whaf, "innocent" sensations. image from Wired, which reviewed Cafe ArtScience here.

Other devices followed Le Whaf: a miniature version dubbed the WAHH; the oPhone, a "platform for olfactory communication"; edible containers (I've written about those before). Many of these things seemed "very far from being useful" at first, but now are finding purposes and brand partners.

But here's the thing. I wrote above that Edwards is not a "smooth talker." What I meant is that he didn't at all come across as someone who was selling a bill of goods; his manner had no hint of political or missionary slickness. (I should note here that I paid a couple hundred dollars for the Sensorium dinner, but Edwards' talk before of the event was free.) He was sharing a worldview still in development, speaking from the position of speculation and wonder rather than certainty and known success. Nonetheless, despite his repeated insistence that the work of Le Laboratoire was not product-development-oriented, he kept drifting back to speculative applications of these sensory technologies, justifying them especially in terms of health care outcomes. What emerged was an irreducible tension between the spirit of free play and non-goal-oriented exploration — what he described as a "willful innocence" of scientific discovery — and the more typical hyperbolic claims of start-ups.

For instance: "Olfaction may be really relevant to how we assess health and deliver health care," he told us during his talk. He wondered aloud: perhaps "health" itself could be "delivered through the air." But when asked to clarify what he meant during the Q&A that followed the talk, he invoked the now-familiar keywords of our VC-driven age: platforms, apps, data. Platforms will soon be introduced, he said, that will collect and analyze the data you generate through interactive apps, connecting variances in your odor sensitivity with changes in the state of your health, which can help assess your risk for ailments such as diabetes. In other words, more or less the same thing every other device we are burdened with is doing: monitoring, quantifying, assessing. Perhaps this is a better, more pleasant way of keeping track of our bodies for medical science; but it's not a revolution so much as a scented cushion.

The big question for me is whether the free-wheeling, playful, non-commercial, improvisatory spirit that seems to drive Edwards' vision for Le Laboratoire can itself be sustaining, or whether it has to continually show its work, justify its purpose, make products to brand and buy.

***

After the talk, as we dutifully stood in line to take our little sips of cloud, clutching our special notched straws, the scene illustrated one of the stubborn challenges of exhibiting non-visual, non-aural sensations. Namely, this: you and I are never sipping a cloud together. Nor are we sniffing the oPhone together. We each wait our turn. And then, after we've taken a sip, or a sniff, we find that we have little we can say about it.

The man ahead of me bent to sip, and came back up again. "Is it very subtle?" he asked the attendant operating Le Whaf. The attendant furrowed her brow. "Not really..." she said. "Let me see your straw." She checked to make sure he was sipping from the right end, and invited him to try again. "Just inhale it into your mouth," she instructed, "like a cigar. Don't draw it all the way down into your lungs."

He gave it another shot. "Hmm." I could tell he was still not sure he was doing it correctly. He turned to me, and shrugged. "Interesting."

He did not know whether or not he had experienced the thing he was supposed to have experienced — whether he had, in fact, experienced anything at all.

He probably hadn't gotten the full effect, because when I took my sip, watching as cloud in the glass chamber narrowed into the channel of my straw, the sensation was powerful enough that I almost coughed.

I believe the one we were trying was "Metal" — described as a mixture of tea and grappa — and it had a kind of sharpness, a floral brightness, that I would agree was metallic (though I perhaps would not have thought it so, if the name had not suggested it). (The others we sampled were Stone Fruit, Jasmine, Rhum Agricole, and perhaps one other that I neglected to write down.)

But still, even as a person who spends the better part of her days trying to figure these things out, when I turned to my husband after he had his turn, we found we had little to say to each other about it besides, "Wow." And, "Did you like it?" We agreed that it was "really interesting."

Is this linguistic poverty about scent (and flavor) one of the things Le Laboratoire's work could address? Do gadgets like this (and Le Whaf really is a gadget, in the classic sense) owe their appeal to their novelty, and thus forego the chance of becoming commonplace and routine (in the lives of those of us who are not pro coffee-cuppers, at least)? Or is this envisioned as a potentially quotidian technology, one that could find a place in already crowded kitchen cupboards, as a mechanism for the delivery of guilt-free sensory indulgences? Simone Weil famously wrote that "the great sorrow of human life is knowing that looking and eating are two different operations." Heaven, for her, was a place where looking and eating were one, where you can have your cake and eat it — ie, where knowledge can be had without loss. (Weil, a kind of saint, starved herself to death.) Is part of the difficulty in understanding the potential place of Le Whaf that we don't yet have the social and cultural frameworks to situate this kind of experience, that all our pleasures have to be reckoned as a line-item in our moral accounting? Or is my frothy, boiling-over brain missing the obvious: it's just for fun, Nadia, relax.

Rachel Field demonstrates the oPhone. Image from Wired, where you can read more about the oPhone here.

This brings me to another device we were given a chance to sniff at: the oPhone. The oPhone was described as a "communications platform," which allows for interpersonal messaging via odor; ie, you can send a smell to the one you love. It's conceptually very clever, undermining the conventional understanding of odor as a "proximity" sensation; spooky smell action at a distance happening here. The oPhone, as an object, includes a base and two columnar tubes, which look a bit like the cooling towers on nuclear reactors. You sniff at the top of one of the columns to receive the scent. The effect is not general — this is not like one of those Glade plug-ins that makes your bathroom smell like orange potpourri — but personal, close-range, intimate. You program the scent you are sending with an accompanying app, keyed to the particular notes contained in cartridges called oChips. More than 300,000 scent combinations are currently possible.

It seems to me that the most exciting thing about a gadget like the oPhone is not that it might allow us to be more articulate about odor, but more articulate with odor. Just as emoji are not decadent nonsense, not a decline from actual language, but a new expressive resource for communication, the oPhone could also be a way to expand the things we are able to express, the meanings we can conceive of and convey.

And also that it could permit communication that is intensively personal and inscrutable to outsiders: the meanings and associations you and I develop with this toolkit, with this set of odors estranged from objects and abstracted from causal circumstances, can develop into precise units of meaning between you and I, which no one else can really guess at, a machine to create and court unspeakable sensations.

***

In 2012, the Museum of Art and Design in New York hosted an exhibition entitled "The Art of Scent: 1889-2012." Curated by Chandler Burr and designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (of Blur Building, Boston ICA, and Highline renown), the exhibit presented a dozen perfumes from Guerlain's Jicky (1889) to Untitled (2010) by Daniela Andrier for Margiela.

The exhibition space was dimly lit and spare. There was a polished wood floor and a white wall marked by a series of depressions, as though a giant, gentle thumb had been pressed into soft clay. Next to each of these depressions, an explanatory paragraph was beamed, naming the perfume and saying a bit about its creator, its elements, its meaning in the history of modern scent.

Exhibition view, "The Art of Scent."

To smell the perfume, you half-ducked your head into the concavity, triggering the release of a puff of odor from a cleft at the base of the hollow. As you inhaled, the explanatory text faded away, signaling to other visitors that that station was in use, but also leaving you, for the moment, to your own senses. You could not also be reading about what you were smelling as you were smelling it.

The mechanics of sniffing.

There was also something delightfully, irresistibly lewd about lowering your head and flaring your nostrils toward the cleft, and hearing that little gasp of perfume releasing. It added a top-note of indecency and decadence that paired well with the austerity of the space, and that brought out the tension between the intimacy of smelling and the public circumstances of doing so.

"The Art of Scent" was organized to advance a particular argument: that the introduction of synthetic chemicals into perfumery transformed what was a craft into an art. When perfumers were limited to natural ingredients, they were more or less limited to the goal of "realistically" recreating odors found in the natural world. Synthetics "radically transformed the medium, by expanding the perfumers' palette and range of artistic expression." (I'm quoting here from the exhibition booklet). No longer were perfumers limited to recapitulating known scents; they could now produce unprecedented sensations, sensory abstractions, emotional phenomena, new ways of being in the world, that aligned with contemporary developments in visual art.

These new synthetic chemicals, "The Art of Scent" proposed, made possible new kinds of actions and reactions, new thoughts, new feelings.

More concretely, however, they made possible new luxury commodities, at once intensely personal ("my signature scent," not at all like the tuberose that old ladies dust their kerchiefs with, but enigmatic, penetrating, dazzling; unfamiliar now, but soon you'll come to associate it with me, and the memory of me) and proprietary, branded. A new kind of thing to buy that can eloquently tell the sniffling world who I am, without sparing a word.

***

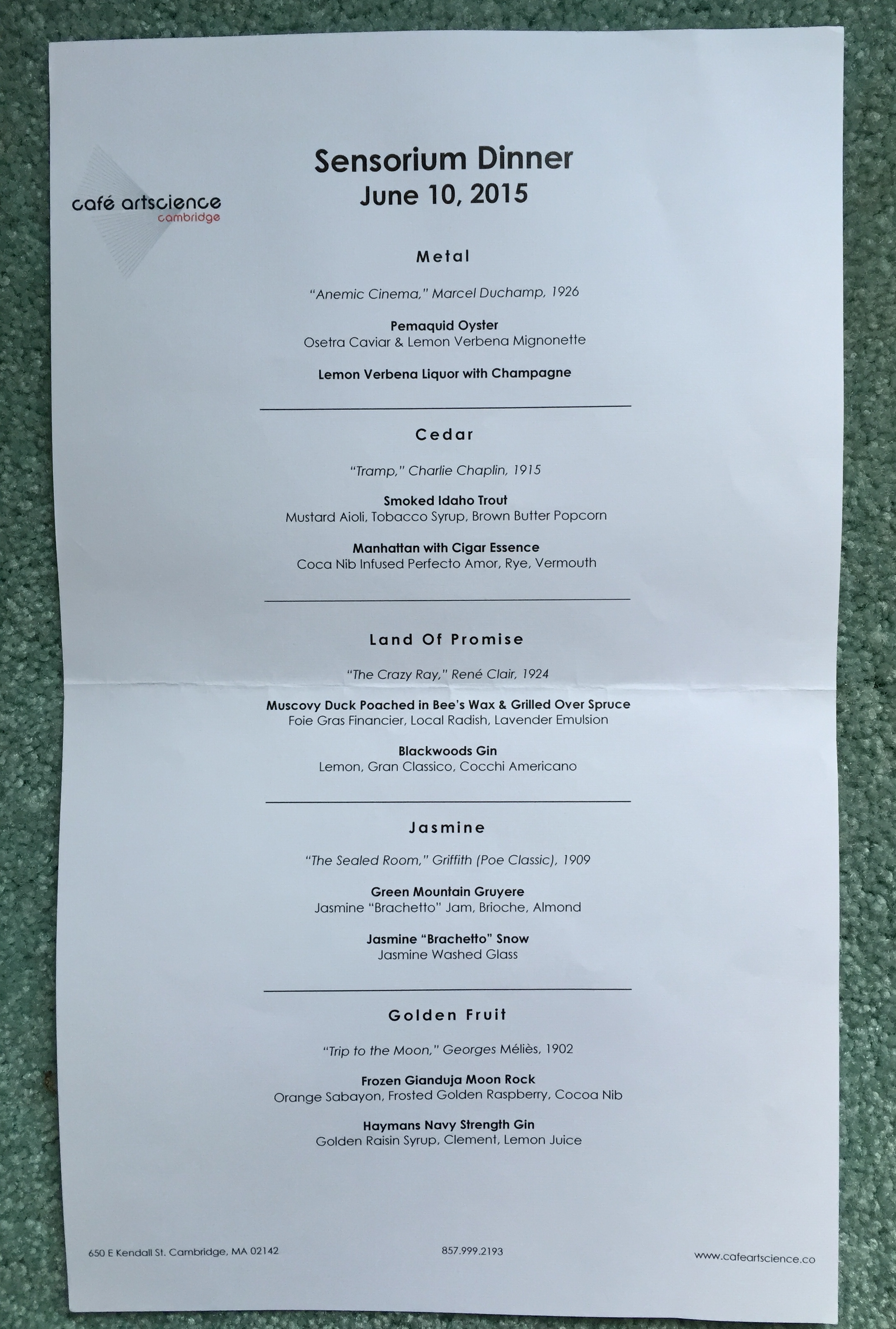

Each course of the five-course Sensorium Dinner came under a thematic heading:

Metal :: Cedar :: Land of Promise :: Jasmine :: Golden Fruit

Each dish was paired with a drink, with a silent film, and with an oPhone odor. These pairings were engineered by Rachel Field, chef Patrick Campbell, and bartender Todd Maul, who also provided the unobtrusive soundtrack for the evening.

The menu of sensations at the Sensorium Dinner, June 10, 2015.

The oPhones waited on pedestals, behind the round tables. At the beginning of each course, the oPhone would emit what was described as the olfactory equivalent of "silence," to wipe clean the sensorium's slate.

Conversation around the tables was lively, strangers becoming instant comrades, and the food was delicious. Nearly a month later, I can still vividly call to mind the taste of the brown buttered popcorn emulsion, an unctuous glob the color of hay that ornamented the slab of smoked trout in the second course.

But it was unclear, deliberately so, how to integrate the concurrent events of the dinner. In particular, the social choreography of visiting the oPhone was tricky. Should you stand up, at a lull in conversation, and wander over to the oPhone? Smell, look, eat, talk? There was a lot going on, and it was at times a bit overwhelming.

On reflection, though, this lack of integration was one of the strengths of the event. Your experience was not directed or controlled, but you were left to your own devices in a pleasure-scape replete with sensory stimuli, a place where the density of experience was deliberately increased. Aside from the sequence of courses, there was no plan or pattern, no key to unlocking the connections between one element and another, just talk and action and sensation, altogether. Edwards had talked about his project at Le Laboratoire as a kind of "experiment," by which I take it he meant that there was no foreordained or hoped-for conclusion.

This meant that the event was, in a way, liberated from the kinds of concerns that have come to attend the sort of self-concious foodie-ism that I sometimes indulge in. Am I doing this right? Am I as sophisticated as these other people here? Am I saying the right thing about this wine, or do I like drinking wine way, way too much to bother with talking about it? What is this going to do for me, how is this going to improve me, enrich me, make me better?

Set all that aside. This was not eating towards self-improvement. It was free play, with food and old movies, and it was disorienting, deranging, and excellent.

***

In the 1930s, the US Chamber of Commerce promoted a program of "sell by smell," recommending that manufacturers add pleasant aromas to dry goods in order to stimulate flagging consumption and motivate Depression-era Americans to buy, buy, buy. An example: identical stockings, some unscented, some scented with narcissus, were offered to Utica shoppers. The narcissus-scented stockings far outsold their odorless twins, and housewives judged them to be of far finer quality.

"Sell by smell" is a moment where the conception of the rational consumer — who can be convinced by reasonable arguments about the material virtues of a product, its durability, its excellent price — gives way to the seduce-able, susceptible consumer, the consumer whose unconscious drives and motivations must be mapped, tapped, exploited.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons for the lingering suspicions that attend scents and flavors. Their actions upon us are compulsive, undetected, and out of our control, often leveraged against our better interests to profit some large entity. The fear that our senses command us.

Yes, and also: in the present moment, innovation, creativity, "disruption" are all virtues of the highest possible value. And these are virtues that are associated with a kind of transcendence of mere rationality. We typically understand creativity as compulsive, out of our direct control, produced, in fact, by scaling back control. Our myths of innovation emphasize the sudden, unannounced insight — the eureka from the bathtub. How do you induce the state of mind necessary for invention to take place? How do you make yourself more creative?

Odor, understood as exerting a kind of direct-action on the brain's unplumbed reaches, an unconscious and powerful agent that produces a spectrum of emotional states, fits neatly into popular intuitions of how creativity happens. This is where Narodny's experiment comes from, and where, I think, Edwards derives his fascination with scents. (There are many senses in the sensorium, after all, but the projects of Le Laboratoire seem oriented around one of them.)

And it's right here, I think, that the central tension in this story, lies: between control and its opposite, between what can be comprehended scientifically and what exceeds those boundaries.

I go back to one of the first things that Edwards said in his talk: "We are starting to understand how to control sensorial experience so that we can lead better lives." Or Narodny speculating on the tremendous value of understanding the neurochemical conditions underlying creativity.

Is the potential here in the improved control, in commanding our senses, or in the liberation from known limits that sensory experience seems to make possible?

And moreover, what kind of scientist gets drawn into this realm? What sort of person does odor attract?

This whole time, I've been dying to tell you more about Leo Narodny, who I first encountered in the pages of Perfumery & Essential Oil Record, where he was a frequent contributor in the 1950s.

This is what I've managed to piece together about him: his mother was a lieder singer. His father was some sort of Estonian art-critic-bon-vivant who changed his last name to Narodny ("Of the People") after befriending Lenin in St. Moritz (those were the days), but fled to America in 1905, ultimately betrayed by Communism. Young Leo, born in New York, 1909, a graduate of Horace Mann and Columbia, trained as an optical physicist, but bought a vanilla plantation in Dominica in 1941, and appears to have resided in the Caribbean for much of his life. He held multiple patents for photography, holography, and information technologies, and turns up in the annals of the International Atomic Energy Agency, where he is thanked for loaning a device called the "Narodny Ion Accelerator" to a lab in Manitoba. At some point in the 1970s, he produced a weekly science series on the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation's version of "60 minutes," where he championed the "small is beautiful" ethos, promoting local technological improvisations and practical tinkering. In the early 1990s, writing in Leonardo from a place called "Enchantment" (Barbados), he proposes a "quantum mechanical theory" of observation to explain how the presence of an audience stimulates artists and scientists to produce their finest work. He claimed to reliably know who was calling before picking up the phone; perhaps some vibration in the telephone wire? Apparently, he also once investigated ESP in insects, trying to discover how ants learn of the death of a distant queen. He died in 1999.

This guy was not a kook, though he did some kooky things. He was a scientist, an engineer, but impelled toward studying elusive, intangible, and unmeasurable conditions of perception and consciousness, of invention and performance.

I know much less about David Edwards' background, but like Narodny, he seems to be someone most comfortable between disciplines and realms — hence the hybrid ArtScience of the cafe's name — but also between ideas and practice, materiality and immateriality. Le Laboratoire has without a doubt whipped up some cool gadgets, but it's clear that Edwards sees his mission as something more transformative than the production of a set of clever and delightful toys. I think what he wants is for Le Laboratoire pioneer a new way of making not just technological change, but cultural change. Despite some of the unresolved contradictions I've gone on about here (at excessive length, surely), that's what's truly exciting about this whole delectable mess, and what is most elusive and unpredictable about it.