How would you make the card catalog for a library of smells?

Organizing smells presents a different set of challenges than organizing books, but it's helpful to think about what makes a library useful. The ideal library is one where a reader can not only locate any item she is searching for, but also where each new item that enters the collection has an uncontroversial position among the shelves. The location also tells you something about the book. Nestled in a cascade of hierarchical, branching categories, the placement tells you what kind of book you're looking at, what its fellows are. Thus, every library inevitably has an ideology; its organizational logic tells you what kinds of things hang together, what kinds of things do not. A library's system not only demonstrates principles of similarity and difference, it defines them.

So how would you decide where to put the odors on the shelves of the smell library? By source or association (plants, bodies, industrial processes)? Odors themselves disrupt this design, promiscuously appearing in all kinds of places. The same smelly chemical can be found in diverse haunts -- feet and cheese, gasoline and grapes -- not to mention chemicals that are synthetically assembled in a laboratory. So how about by "type" (fruity, green, smoky)? You run into the problem of defining these types, and their boundaries – which makes the smell library less useful to smellers without prior experience in the system. What about by chemical structure or group (aliphatics, aromatics; aldehydes, esters)? This might tag a stable fact about the material substrate of a smell, but it sidesteps the experience of it. Chemicals in the same structural group can have radically different odors; even chemical isomers (that is, molecules that are mirror-images of each other) sometimes differ dramatically in how we perceive them. And none of these systems are much help if you have an unknown smell, of unknown origin, that you need to identify.

As far as I can tell, there is no equivalent to the good old Dewey decimal system or the Library of Congress cataloguing system for organizing smells and flavors. Perfume and flavor materials are grouped in different ways for different purposes and different kinds of users.

The passions of Ernest Crocker, "first man in the U.S. to classify odors scientifically," from Robert M. Yoder, "The Man with the Million Dollar Nose," Saturday Evening Post, September 29, 1951, p. 27.

This is one of the reasons I'm so interested in an early, failed attempt at classifying the world's stink and splendor: the Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification System, and its co-developer (and mastermind) Ernest C. Crocker (1888-1964).

The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification System claimed to be able to index the entire smelly world with a set of four-digit numerical codes.

The Smell of a Rose: 6423

Fresh-Roasted Coffee: 7683

Ernest Crocker and Lloyd Henderson began developing their system in 1917, during the First World War. Young chemists working for the US Army's chemical warfare division, they spent their workdays concocting foul-smelling but harmless gases intended to bamboozle the enemy into a false sense of security. The stink of their chemicals was indelible – it clung to their hair, skin, and clothes – and so at night, they slept outside, stretched out under the stars, plotting a scheme for a taxonomy of odors. (These details come from a September 29, 1951 profile of Crocker in the Saturday Evening Post, "The Man with the Million-Dollar Nose." As with many stories about Crocker, it's difficult sometimes to tell truth from legend.) Their system was first aired publicly in the 1920s – when both were working at the Arthur D. Little Company, in Cambridge, a pioneering research and consulting firm.

Jasmine: 7643

Napthalene: 4564

The first part of the Crocker-Henderson system is based on the following proposition: just as there are three primary colors, there are four primary odors. And just as every color that we perceive in the world is an interpretive effect, produced by wavelengths of light differentially stimulating the three different kinds of chromatic receptors in our retinas, every actual smell in the world is a mixture of the primary odors, triggering the (hypothesized) nerve receptors that are susceptible to them.

Crocker's odor standards at Arthur D. Little. From his 1945 book, Flavor (New York: McGraw-Hill).

According to Crocker and Henderson, the primary odors are:

1. Fragrant

2. Acid

3. Burnt

4. Caprylic

The second part of the system is based on the intensity of these primary odors. Crocker and Henderson detected eight step-like gradations in intensity for each of the primary odors: 0-8. (There are no fractional amounts in this code, only integers.) Each of the primary odors is experienced differently depending on its intensity, just as the color red can range from Revlon's "Nude Attitude" to "Cherries in the Snow" depending on how saturated that red is. And just as "Nude Attitude" makes a very different moue than "Cherries in the Snow," the primary odors have a different character at low and high intensity.

Fragrant smells include the sweet smell of various flowers, but the most intense expression of "fragrant" is animal musk. Acid smells range from the sour smells of certain fruits to the more acrid scent of vinegar. Burnt odor, according to Crocker and Henderson, is present at middling intensity in citral, which you'll recognize as the smell of lemongrass, and at its highest intensity in woodsmoke and roasted coffee.

Caprylic is a word that you'll be glad to learn if you don't already know it: it means goaty. The smell of sweaty bodies, wet dogs, shit, gasoline. "A generally unpleasant sensation when strong, yet much missed if nearly absent," notes Crocker.

This matrix of four primary odors and eight intensity levels allowed them to code odors according to a "semi-qualitative" numerical system. Here's how it worked. Crocker and Henderson would analyze each sniff, mentally separating it into its four primary components, then judge the intensity of each component on a scale from zero to eight.

Styrax: 5222

Ylang Ylang: 8433

According to the Saturday Evening Post's profile of Crocker, 1111 is a "nonentity in odors, light in everything" – (perhaps the "white noise" of smells) – while 8888 is "a thunderclap of an odor, potent in every way possible." (Diacetyl was cited as an approximation of this theoretical stink, comparing its smell to "the burning wreckage of a building which had been inhabited by wet dogs, skunks and goats.") These two poles were the theoretical experiential limits – the smells of our world all tallied up in-between.

Crocker would sometimes telephone Henderson and call out a number: 6443! 8257! Henderson would have to guess what it was – Old grapefruit rind? Tomato sauce? Shaving lotion? Most times, according to Crocker, Henderson would be right. They would go on "smelling binges" in the Arnold Arboretum, putting a number to each blossom.

But the method had little value as a private game. In order to be validated, it had to come into public use – serve as a means for different people to communicate effectively about odors. Crocker and Henderson compiled a catalog of more than 500 smells-by-number, but as a reference, it had little utility except to others trained in the system.

Enter the Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification Set, for sale from Cargille Scientific Supply (118 Liberty Street, NYC, NY) beginning in the mid-1940s. The kit comprised a manual, "Scientific Odor Control," and a set of 32 sniffable glass vials, each filled with a substance representing one of the four basic odor sensations at one of eight recognized increments of intensity. (The ninth possible increment - zero - was implied.)

The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification Set, sold by Cargille Scientific Supply. From Alden P. Armagnac [yes, that is a real name!], "What Is a Stink?" Popular Science, March 1949, p. 147. An amazing article that has some more background on this stuff, and available free on google books, which is not always evil.

How did you use it? When smelling a new, unclassified thing, the operator would sequentially isolate each of the four component primary odors, judging first how fragrant it was, then the intensity of the acid odor, then of the burnt, and finally the caprylic. The "standards" in the kit were for reference. Not sure whether your sample had a level 5 or level 6 burnt odor? Grab a whiff of the two relevant standards, compare with your sample, and make the call.

Note that the standards in the kit were not "pure" unmixed examples of the particular odor and intensity. That is to say, the standard for "burnt level 6" was not 0060; it was 6665, thujone. The operator would be expected to analyze the standard scent to isolate the odor intensity needed as a referent. Some chemicals thus served as standards for more than one odor intensity; vanillin, for instance, represented both level 1 fragrant and level 2 caprylic.

Lemons: 6543

Camphor: 5735

Are you confused yet? I'll add that the system was not supposed to be restricted to olfactory geniuses and hound dogs. Anyone was supposed to be able to learn how to use it, and become a competent smell analyst. "It should be sufficient to learn a few elemental types," Crocker explained in 1935, "as the colors are learned in sight, or the tones in sound." While professional perfumers might be able to memorize hundreds or even thousands of individual smells – to compose grand chords on the "perfumer's organ" – an adequate classification system should be usable by non-experts who are looking to recognize unknown and unpleasant odors, to address smell and flavor problems as well as produce smell and flavor fantasies.

In his 1945 book Flavor, Crocker insisted that it was "easy, even for beginners, to smell for any one component such as acidity, concentrating on it so completely that the other components seem to have vanished momentarily during the sniffing." Once trained in the system, a student could make up to 60 analyses before nasal fatigue set in. An hour's rest would prepare the operator's learned sniffer for another round.

Vanillin: 7122

Lavender Flowers: 7524

Who was expected to buy this thing? According to Cargille Scientific Supply, it was used by: "oil companies, distillers, soap and food manufacturers, the Army, the Department of Agriculture, and university laboratories." The system was used (unsuccessfully) by the EPA to try to classify industrial odors in Louisville in the early 1970s. It was also used by an entomologist in the 1950s to study olfactory perception in cockroaches' antennae; he used the standards as his experimental samples. The set was touted in a 1950 police science technical journal, which observed: "Odors frequently play a part in the identification of traces of material; therefore, police technicians will find the Henderson-Crocker Odor Classification Set useful for the analysis of stench bombs, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, etc." A Crocker-Henderson-savvy detective might enter a crime scene and sniff the air for an elusive trace of cologne, a piece of evidence that literally evaporates, and assign it a number. A technician could later look up the number and proclaim: the suspect wears Polo, by Ralph Lauren.

So did it actually work?

Unfortunately... not really...

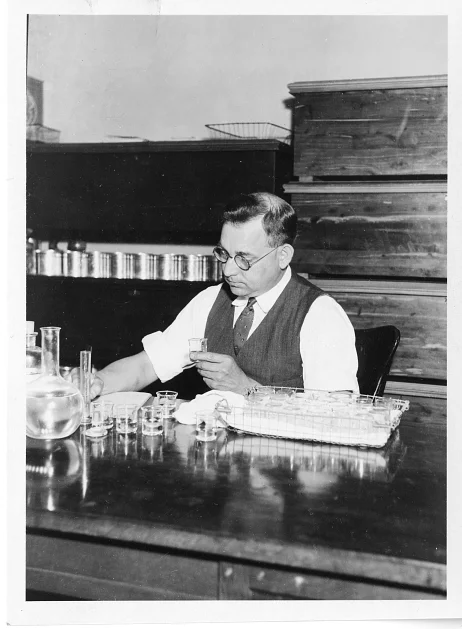

Ernest C. Crocker getting busy. From the Smithsonian Institution Archives: Acc. 90-105 - Science Service, Records, 1920s-1970s.

In 1949, two Bucknell psychologists – Sherman Ross and A.E. Harriman – published the results of a study of 30 college students, self-identified as having a "fairly good" sense of smell, who were presented with the 32 unlabeled vials in the Crocker-Henderson kit. Half of the subjects were asked to arrange the standards in as many groups as they thought appropriate – testing the premise that there are four self-evident primary odors. The other half were given the primary odor categories, and told to organize the standards in order of intensity. In both cases, the students failed miserably to replicate Crocker and Henderson's results.

Further, Ross and Harriman took issue with Crocker's assertion that the samples were "harmless." "Several of our [subjects] had severe headaches from their participation in the experiment, and one was affected markedly," they chided. The Crocker-Henderson Classification system, they concluded, was "judged to be inadequate."

Clove oil: 7563

Phenylacetaldehyde: 6633

Henderson left Arthur D. Little to work as a chemist for Lever Brothers soon after developing the system, but Crocker continued working for the company until the 1950s, specializing in problems related to odor and flavor and pioneering methods for identifying and correcting "off-odors" (and "off-flavors") in foods, household goods, and industrial sites. Does your bakery's bread taste inexplicably fishy? Is your factory stinking up the neighborhood? Call Crocker!

Although there were some odors that he admitted he couldn't stand (cooked cabbage), Crocker was ecumenical about smells. He was interested in the whole stinking world, and believed that a coherent system for naming and understanding odors would make the public more broad-minded about unfamiliar smells. As he wrote in a 1935 article in Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, with the advent of a "real language of odor.... will come more odor-consciousness and accuracy. No longer will the unknown odor be automatically treated as suspicious or unpleasant, but will be describable for what it is."

Crocker's analytical-numerical system would be supplanted in the late 1940s at Arthur D. Little by the "Flavor Profile Method," where a panel of individuals trained in sensory methods arrived, by consensus, at a linguistic description of the holistic sensory dimensions of a thing. Unlike Crocker's system, the Flavor Profile accounted for diverse sensory modalities (feel and sound as well as taste and smell), and could also make note of the temporal aspects of sensory experience. The aftertaste of a toothpaste. The first bite of a biscuit. Like the Crocker-Henderson system, it claimed to be objective, reproducible, accurate, scientific. Unlike the Crocker-Henderson system, it could not summarize the sensory world. It was a portrait, not an index.

Crocker by all accounts was a persuasive, if sometimes brusque, man: ambitious, imaginative, prolific. During the Second World War, he worked for the Army developing techniques for baffling bloodhounds. He astounded a corporate client by reconstructing the multi-step manufacturing process of silverware – identifying the source of a foul odor – just by sniffing their forks. He once grew a gigantic lemon in his garden on Nantucket. He was a memorable and compelling speaker, who loved talking to the press and gladly accepted speaking engagements to address scientists, industrialists, and the public at large. As Loren Sjöström, Crocker's successor at the Arthur D. Little Flavor Laboratory, recalled in 1976, more than a decade after his death, "Even to this day, people will say, 'I remember hearing Crocker back in St. Louis talking about flavors.'"

Clary Sage: 5643

Moth Balls: 4564

I admit I have a soft spot for the Crocker-Henderson system, even if I find it baffling and impracticable. I also like that it casts a synesthetic aura upon the normally scentless world of numbers. As Arthur D. Little (the man himself!) joked at the 1927 company Christmas party, Crocker "can analyze any smell and give it a numerical designation which discloses its components. I suppose it’s the same way with dates and telephone numbers. It has its disadvantages – think of calling up a refined and attractive girl whose telephone number suggests a mixture of burnt leather and garlic with a little rancid fish oil and just a touch of coal gas. It isn’t fair to the girl.”

![The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification Set, sold by Cargille Scientific Supply. From Alden P. Armagnac [yes, that is a real name!], "What Is a Stink?" Popular Science, March 1949, p. 147. An amazing article that has some more background…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/520a3a3ee4b04f935eefceef/1408987898623-BT0VAU73A3UVIPNC1BMA/Crocker-Henderson+Odor+Classification+Set)