Line your lairs with slices of white bread: the great mayonnaise wars have begun!

You may have heard the news that Hellman's, a subsidiary of Unilever, is suing Hampton Creek over a rival product, Just Mayo. Their claim? Just Mayo is a phony trying to pass itself off as the real thing. As one of Unilever's VPs told Businessweek: "They're nonmayonnaise and are trying to play in the mayonnaise side."

At issue are FDA regulations that officially define what can legally call itself mayonnaise in this country. These regulations decree mayonnaise to be an emulsified semisolid food that must contain three things: vegetable oil, an acidifying ingredient (vinegar, lemon and/or lime juice), and egg yolks (or, technically, an egg-yolk-containing ingredient).

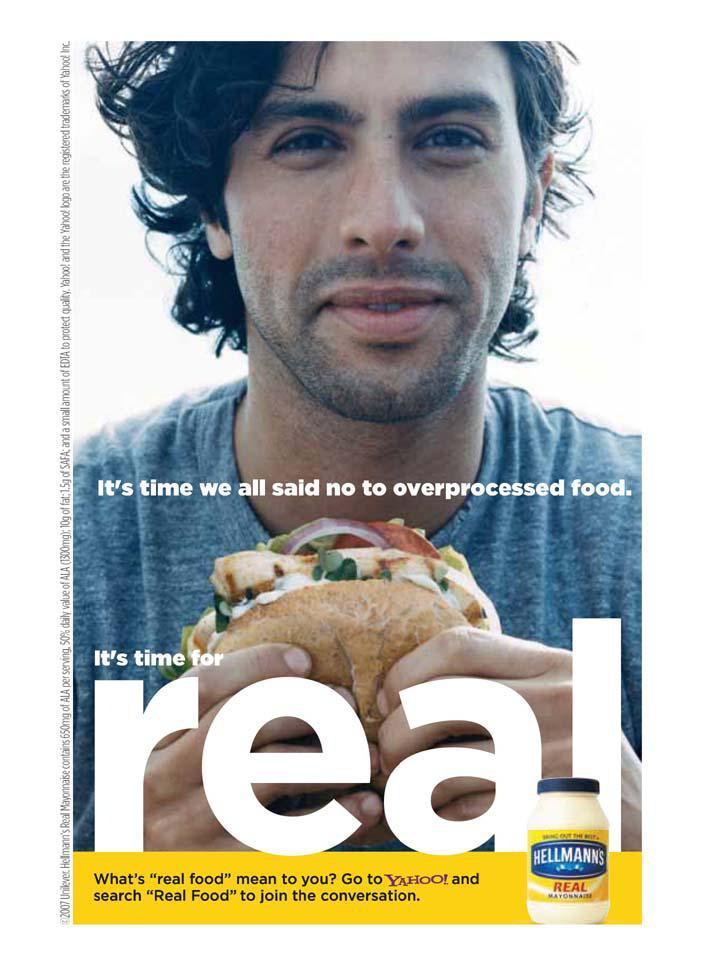

Hellman's: It tickles the menfolks!

The regulations also specify a suite of optional ingredients that can be included in without mayonnaise sacrificing its legitimacy -- salt, MSG, crystallization inhibitors such as oxystearin, etc. -- but the egg yolks are the sticking point here.

My name is 'Mayonnaise,' emulsion of emulsions

Look upon my yolks, ye mighty, and despair!

Hampton Creek makes a vegan, entirely plant-based product. There's a joke that goes: "How do you know if someone is a vegan?" "Don't worry. They'll tell you."***

Hampton Creek is not that kind of vegan. Josh Tetrick, the company's CEO, told the Washington Post: "We don't market our product to tree-hugging liberals in San Francisco.... We built the company to try to really penetrate the places where better-for-you food hasn't gone before, and that means right in the condiment aisle of Walmart." It's evident that Just Mayo doesn't want to get pinned as some hippie "health food," a carob also-ran trying to compete with actual chocolate. It claims to be as delectable as the thing itself. It even features an egg-like ovoid on its label, for some reason.

The media, along with its celebrity chef auxiliary corps, has generally taken the side of the underdog here, chiding Unilever for bullying the start-up and generally acting like the soulless multinational corporation that it is. (There have also been some subsequent ironies -- Hellman's had to change the wording on their website to account for the fact that some of their products, including their olive oil mayonnaise, don't count as mayonnaise either under the FDA's regulations -- like Miracle Whip, another nonmayo, they are technically "dressings.")

But in making this a story about big and little brands fighting over shelf space at the supermarket, the historical dimension of this spat is being ignored.

For that, we'll have to turn to the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act, and the law that it amended and expanded, the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.

The 1906 law is probably best remembered as landmark public health legislation, creating the infrastructure to inspect food and drugs and safeguard their safety. But it also gave the federal government the authority to intervene in preventing fraud by regulating how foods and drugs were labeled and advertised. It was no longer permissible to call your product "Olive Oil" if it was mostly vegetable oil, with a drizzle of olive oil for flavor, or "Strawberry Jam," if its flavor and color came from synthetic chemicals and not actual fruit. These would have to be labeled "imitation" or "compound," black marks against them, in marketer's estimations.

But this did not stop manufacturers from giving fanciful or "distinctive" names to their products, avoiding an explicit claim while making the similarity as implicit as possible. Calling the oil "Spanola--For Salads," for instance, and selling it alongside similar-looking cans of genuine olive oil. This jam-like substance may look and taste a lot like jam, but it's not jam, it's "Bred-Spred"! By the 1930s, a growing number of these novel, fabricated foods were appearing on supermarket shelves, the new self-service stores where consumers were doing more and more of their grocery shopping, making their own choices about what to buy, unaided by clerks or shopkeepers. Note that the issue here was not that these products are dangerous or harmful, but that they seemed to be taking advantage of consumer ignorance -- deceiving well-intentioned housewives into unwittingly buying cheap substitutes for real things

The notorious Bred-Spred is on the right; the other foods shown here are an imitation vinegar and an imitation peanut butter, all sneakily seeking to avoid having to bear the stigma of "imitation" by using "distinctive names." Image courtesy the FDA History Office.

The 1938 law dealt with this apparent problem in several ways. First, it gave the FDA the authority to create and enforce food standards -- official definitions of the constituents and components of staple foods, such as olive oil, or jam, or mayonnaise -- that foods would have to meet in order to be legitimately sold as such on the market. Foods that did not contain the ingredients required by the established standard of identity, or that included components that were not officially permitted as "optional" ingredients, would be declared "misbranded" or "adulterated" and seized by FDA agents.

Second, the law also took action against any food that "purports to be or is represented as a food for which a definition and standard of identity has been prescribed" when it didn't meet the requirements of that standard. This essentially meant that substandard "imitation" foods would no longer be allowed on the marketplace -- everything that acted like jam had to meet the fruit and sugar requirements of jam, and would be prohibited from including additional ingredients (flavor chemicals, for instance) not listed in the standard. The "purports to be or is represented as" phrasing is key here. This is how the FDA took action against foods like Spanola or Bred-Spred. These foods would no longer be protected by their "distinctive names." FDA agents would look at the sales context, label and package design, and intended use of the product to evaluate whether it was attempting to pass itself off as some other, more lovable food. For foods where no standard of identity existed, products would be required to list and disclose all of their ingredients on their label.

Third, the law included a broadly written clause [Section 402(b)] prohibiting manufacturers from adding any substance “to make the product appear better or of greater value than it is… or create a deceptive appearance.” So -- any additives to enhance flavor, color, texture, and so on were suspect.

I won't go into the longer history of the enforcement of this law here -- though if you're interested, read up on the so-called Imitation Jam Case, which scaled back some of its prohibitions -- but I will note that these sections of the federal code were intended to be in the consumer's interest, to ensure that shoppers got what they paid for. They also protected some manufacturers' interests, those who felt that their "genuine" products were being undercut by cheaper substitutes.

It's worthwhile to think about the ideological underpinnings here. The law presumes that imitations products are inferior, but also that consumers can't readily tell the difference. Any modification of a food -- any departure from the standard -- is considered to be to a food's detriment. Additives to improve the flavor or appearance of a food are cast under suspicion, inherently deceitful. When it comes to food, technology is assumed to diminish quality and value rather than enhancing it.

The food industry increasingly criticized the law on the grounds that it straight-jacketed innovation, entombed foods in restrictive standards, and disincentivized progress and improvement. In industry meetings and trade publications, they rolled out a litany of cases that purported to show the absurdity of the regulations. Quaker Oats Farina, fortified with vitamin D, could not be sold as Farina, because it contained added vitamin D, but it also could not be sold as fortified Farina, because it didn't contain other additives required for that standard -- so it couldn't be sold at all! Canned asparagus must be packed in water, the standards stated. So a canner who wanted to pack his spears in natural asparagus juice would be violating the law!

Although the FDA apparently enforced this statute with considerable vigor, by the late 1960s, the agency's position was coming under increasing fire, in part because of the growing awareness of a pair of diet-related health crises: obesity and heart disease.

Riffling through the FDA files on this subject at the National Archives this past summer, I came across a highlighted copy of a May 1970 article from the Food Drug Cosmetic Law Journal. In "New Foods and the Imitation Provisions of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act," William F. Cody, a member of the legal department of CPC International [né Corn Products Company], argued that the FDA's regulations were delaying the introduction of low-fat, lower-calorie foods that could substitute for the fat- and calorie-dense foods that were contributing to overweight and coronary disease. He gave two examples: a low-calorie margarine and a "dehydrated egg" that he claimed had been processed to diminish saturated fat and cholesterol without minimizing the beneficial nutritional components or altering the flavor. According to the FDA, he said, these products should legally be labeled "imitation margarine" and "imitation dried eggs." But, he said, calling these goods "imitation" because they did not conform to standards was actually harmful to the consumer as it "conjured up an image of something highly synthetic or cheapened, and generally discourages broader consumption of these useful products."

The fundamental issue, he argued, was that the context of food manufacturing had changed since the 1938 law's passage. The law assumed that imitation foods, or foods that substituted standard ingredients, were inferior to traditional foods, or at least had lower production costs. That the only motivation for making a substitution would be to reduce costs. Instead, new fabricated foods were not "imitations" in the law's intended sense, trying to find another way to provide the same characteristics to customers at a lesser cost. They were different in critically important ways -- for instance, by being lower fat, or lower calorie -- and marketers emphasized the differences rather than concealed them. They might even cost more to produce, or to buy, than the traditional product. In other words, at least to some consumers, these imitations were superior to the original.

Memos appended to this documented suggested that FDA officials agreed with Cody's arguments.

Which brings us back to Just Mayo. Just Mayo is an imitation of traditional mayonnaise, but one that claims to be superior to the real thing -- it's healthier, it's made "sustainably," it's somehow both a comforting reminder of your mom's favorite pale semisolid emulsion sandwich spread, while also being more sophisticated, somehow, more natural.

To be clear, I don't have a dog in this fight -- I'm one of those people who really does not like mayonnaise. But what interests me about this is how two exceptional examples of processed foods -- reflecting the collaborative efforts of food technologists, engineers, chemists, factory workers, and marketers -- seem to be on opposite sides of the scale of virtue, depending on where you stand. And how a law whose stated purpose was to protect consumers from fraud and deception -- from being bamboozled by the efforts of chemists and manufacturers who could make the fakes seem too convincing, too indistinguishable to the credulous palate -- is now used as a cudgel by a huge manufacturer of perhaps the archetypal processed food, to advance its claim that Hellman's is traditional, is "real," unlike -- I suppose, the surreal fantasy in the key of mayo proffered by its eggless rival.

***I'm iffy on this vegan joke; I justify its inclusion here as cultural context, proof of the ambivalence about what counts as a legitimate reason for eating "good" food. Consumers are supposed to have a sort of political power, but being too "strident" about your reasons for making certain choices makes you the butt of a joke. The fact that Hampton Creek feels like it has to hide its vegan-ness from the mass consuming public makes me think that vegans should actually be more vocal about the reasons underlying their beliefs and actions.