In my former life, before all of this PhD stuff, I spent some time working as a speechwriter. It wasn't the political trenches, exactly; it was more like the political chicken-coop where "messaging" is laid, hatched, and polished under the sweaty, intense glow of artificial heat-lamps. Perhaps as a result, there's something irresistible to me about politics at its grossest, when it's all pandering and bluster, dirty feathers and rotten ugly guts. I'm too squeamish for horror movies, but the Republican primary is the kind of grotesque spectacle that I can't turn away from. (By the way, for those who prefer to imagine the candidates as blobby, expostulating critters, I'll be live-drawing the next debate, September 16, and posting the pictures on Twitter— my handle is @thebirdisgone — and then maybe somewhere on this website.) Nonetheless, the headlines from the race are so bizarro, that I find myself harboring a persistent feeling of unreality.

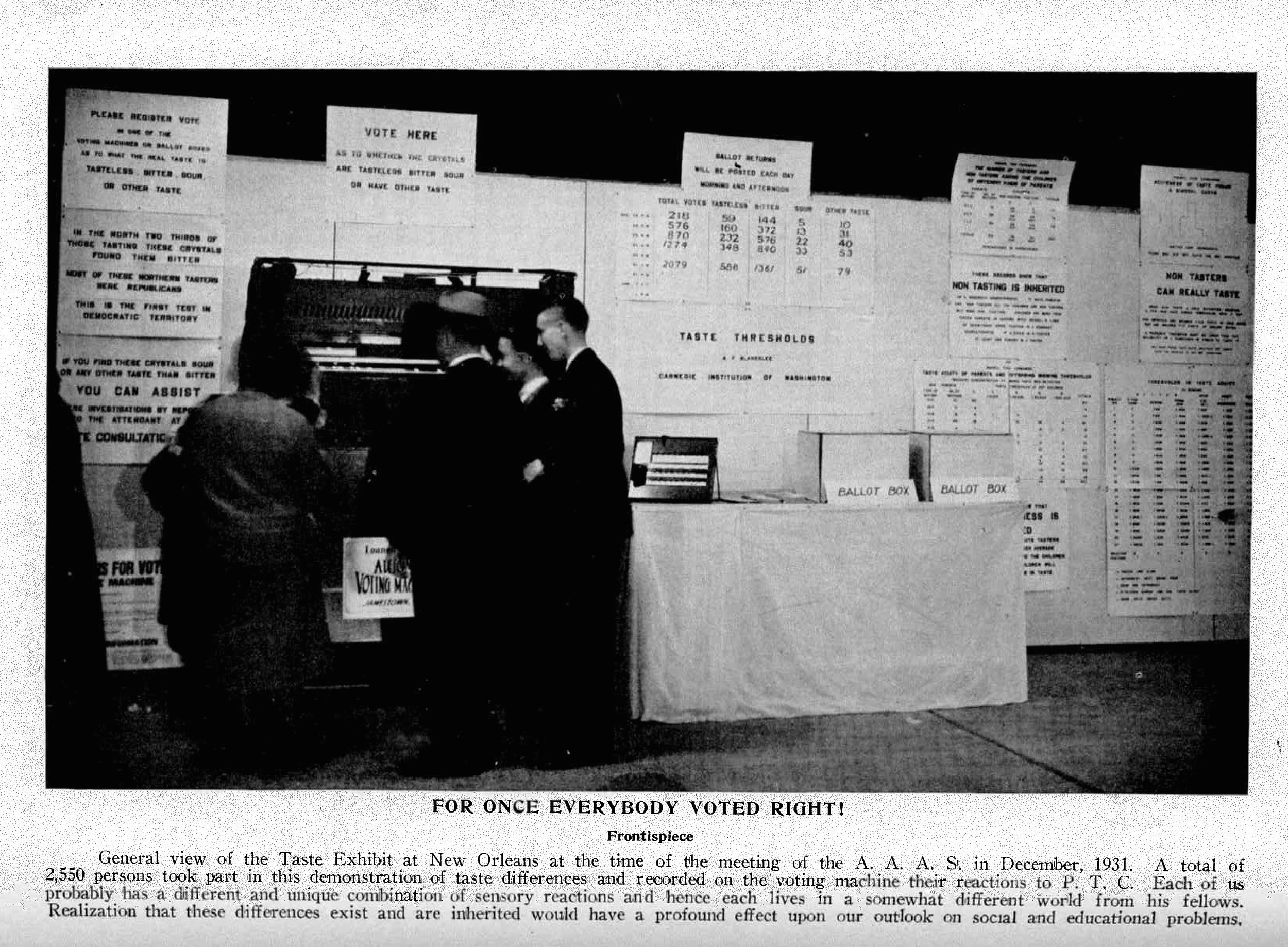

So this blog post goes out to all of you who are also experiencing that queasy sense of doom and despair as the next presidential election draws slowly but ineluctably nigh. Here is evidence of an election where "FOR ONCE EVERYBODY VOTED RIGHT!"

Well, the story is a bit more complicated than the caption suggests. This is a photograph from the 1931 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in New Orleans. What these people are "voting" on is taste — specifically, the taste of phenylthiocarbamide (PTC). Many of you might remember this kind of taste-test from biology class, where it's a standard part of lessons about genetics and human variation. I the day in genetics summer camp (yes, I'm a nerd) when we all placed tabs of chemical-infused blotting paper on our tongues and wrote down in our lab notebooks what we did (or did not) taste. Who else learned that supertasters are picky eaters, and non-tasters are the ones you want at your dinner party? (Full disclosure, I'm a non-taster).

Of course, your tasting abilities, eating habits, and food preferences depend on much more than whether you have a gene for PTC-sensitivity or not. And even though the myth of the "supertaster" — the person gifted with an acutely sensitive palate — persists, the ability to recognize the components of what we taste and smell are largely learned through practice, as this recent piece by Eliza Barclay at NPR illustrates. (For a nice take on the complexities and ambiguities involved in designating someone a supertaster, and the ambivalent relationship between supertasters and wine connoisseurship, check out this series by Mike Weinberger from 2007. For even more on supertasters, take a gander at Mary Beckman's 2004 article in Smithsonian.)

PTC "taste blindness" is possibly the most studied trait in human genetics, according to Dr. Sun-Wei Guo and Dr. Danielle Reed of the Monell Chemical Senses Center. (For an interesting history of PTC in genetics research, see this journal article.) But as the photograph above shows, PTC began to be used in an educational context almost as soon as it was used in scientific research. As a chemical index of human variation, it was from the outset used to support specific social and political arguments about the meaning of these differences. And after all that preamble, that's what the subject of this blog post is: the peculiar intersection of the senses, science, and political ideology illustrated by the spectacle of people voting on the taste of PTC.

PTC's dramatically different effect on different people was discovered, apparently by accident, in a DuPont laboratory sometime around 1930. Arthur L. Fox, a chemist, was messing around with a container of the chemical when some of the PTC crystals wafted into the air. His lab partner complained of their intensely bitter taste, but Fox was unaffected. He tasted nothing at all. How could one molecule produce such different responses?

Fox appears to have been most interested in the relationship between chemical structure and taste sensation, but he also studied the distribution of PTC-insensitivity across the population. "This peculiarity was not connected with age, race or sex," Fox wrote in a 1931 report to the National Academy of Sciences. "Men, women, elderly persons, children, negroes, Chinese, Germans and Italians were all shown to have in their ranks both tasters and non-tasters."

Somehow, Albert F. Blakeslee got wind of these experiments. Blakeslee was a prominent botanist and geneticist at the Carnegie Institution Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor, one of the premier institutions for genetic research in the United States. Cold Spring Harbor was also the home of the Eugenics Records Office, which collected family pedigrees, case studies of genius and deviancy, and other evidence used to shape public and social policy to produce a "fitter" populace.

PTC was probably initially attractive to Blakeslee because it seemed to offer a simple experimental protocol for tracing heredity in otherwise messy and difficult to study human populations. One little taste told you unambiguously whether someone was or was not a taster, and you could mark it on your chart and move on down the family line. Conveniently, PTC insensitivity appeared to be a classic Mendelian recessive trait. About a quarter of tasters were non-tasters. Non-taster parents (homozygous for the recessive) only produced non-taster children. A taster child must have at least one taster parent. But non-taster children could be, and were often, born to (heterozygous) taster parents.

But for Blakeslee, PTC was not only a useful tool for mapping the inheritance of traits. In cheap, "harmless" PTC, he found a perfect pedagogical device both for demonstrating the existence of hereditary differences among individuals, and also for advancing what he called the "genetic view-point" among non-scientific audiences.

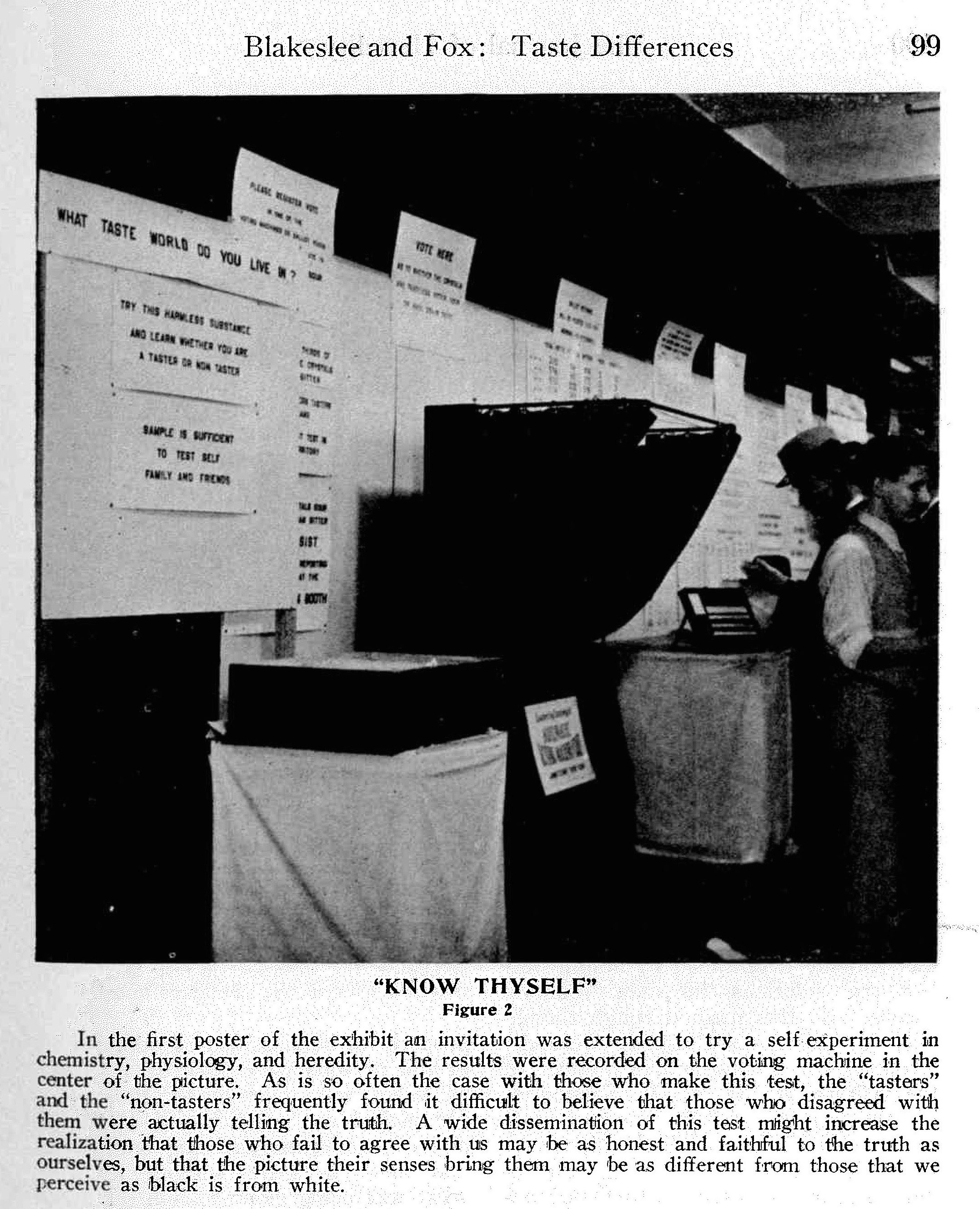

"What Taste World Do You Live In?" "Know Thyself" "Vote Here" ... In the Taste Exhibit at the 1931 New Orleans meeting of the AAAS, messages of self-knowledge, scientific participation, and civic engagement intermingled. Image from the March 1932 Journal of Heredity.

This is the context for the exhibit that Blakeslee, Fox, and other colleagues designed for the 1931 AAAS meeting in New Orleans, the image that kicked off this post. Under a banner asking, "What Taste World Do You Live In?" visitors were invited to "try this harmless substance and learn whether you are a taster or a non-taster." 2,550 people pulled the lever, indicating whether they found the PTC "tasteless," "bitter," "sour," or something else — "other taste." The following year, another 6,000 people voted when the exhibit was reassembled for the Third Eugenics Congress at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

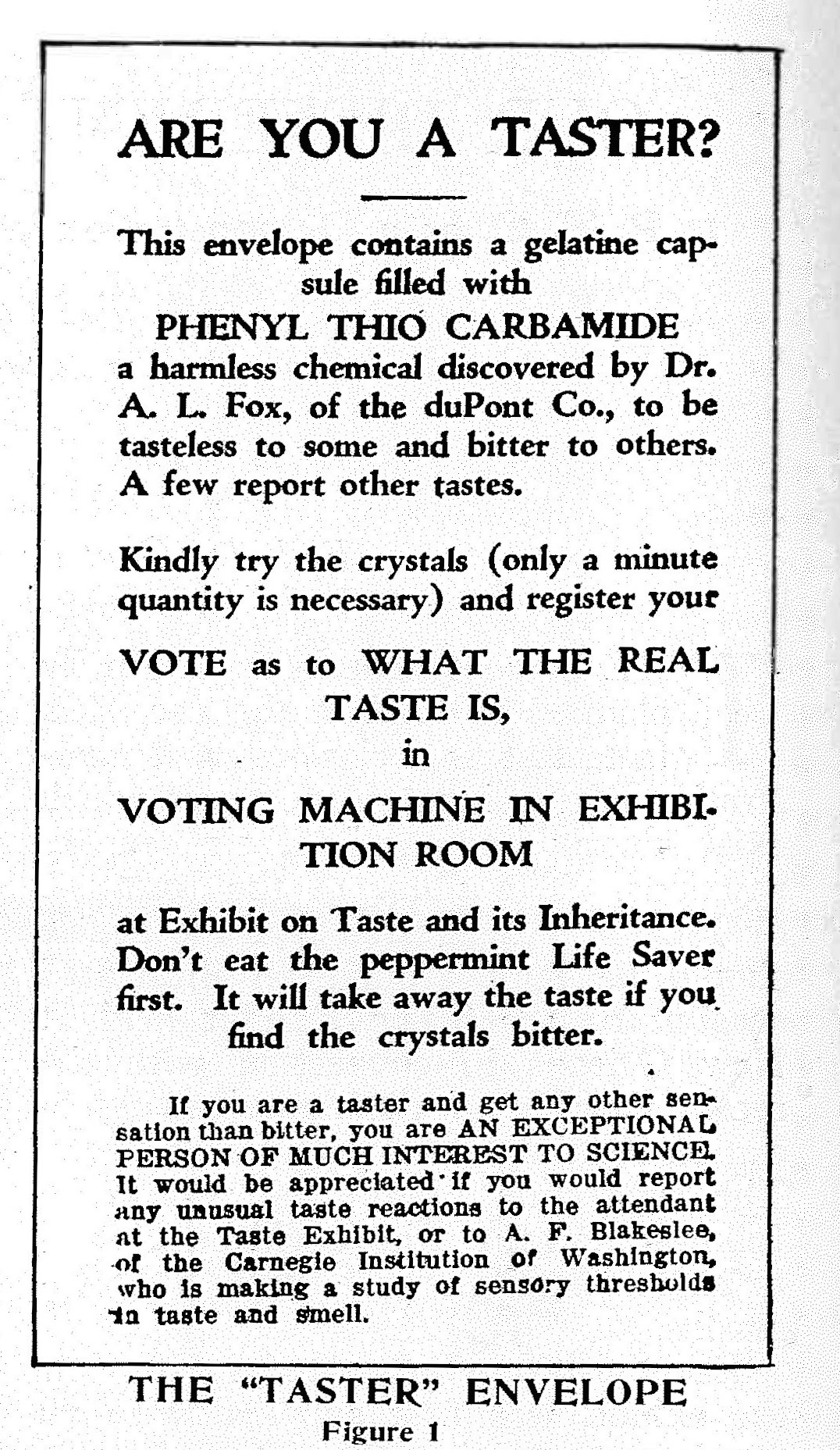

This is the information that exhibit visitors received prior to tasting PTC and voting on it. After tasting, voters could have a peppermint life-saver — but they must not eat it first! As this text makes clear, many PTC tasters experienced the chemical as something other than "bitter." People described their experience of PTC as sour, sweet, or astringent, or compared it to the taste of lemons, rhubarb, cranberries, vinegar, and camphor. Where did these people fit in? They could vote "sour" or "other taste," but their civic-scientific duty was not complete with the casting of a ballot. The exhibit informed visitors who experienced a taste other than bitter: "you are AN EXCEPTIONAL PERSON OF MUCH INTEREST TO SCIENCE" and directed them to report to the "Taste Consultation" booth for further study. In this way, Blakeslee and colleagues discovered various cases of people who could not discriminate between bitter and sour sensations, or who described bitter "incorrectly" as sour, salty, and sweet.

The centerpiece of these exhibits was not exactly the chemical PTC, nor was it any scientific device. It was a civic instrument: the voting machine, generously loaned by the Automatic Voting Machine Corporation of Jamestown, NY. The noisy machine "attracted people in the exhibit hall and undoubtedly increased the number of people who took the test," Blakeslee wrote. Tasters were asked to pull the lever to register the "real taste" of the substance: tasteless, bitter, sour, or "some other taste."

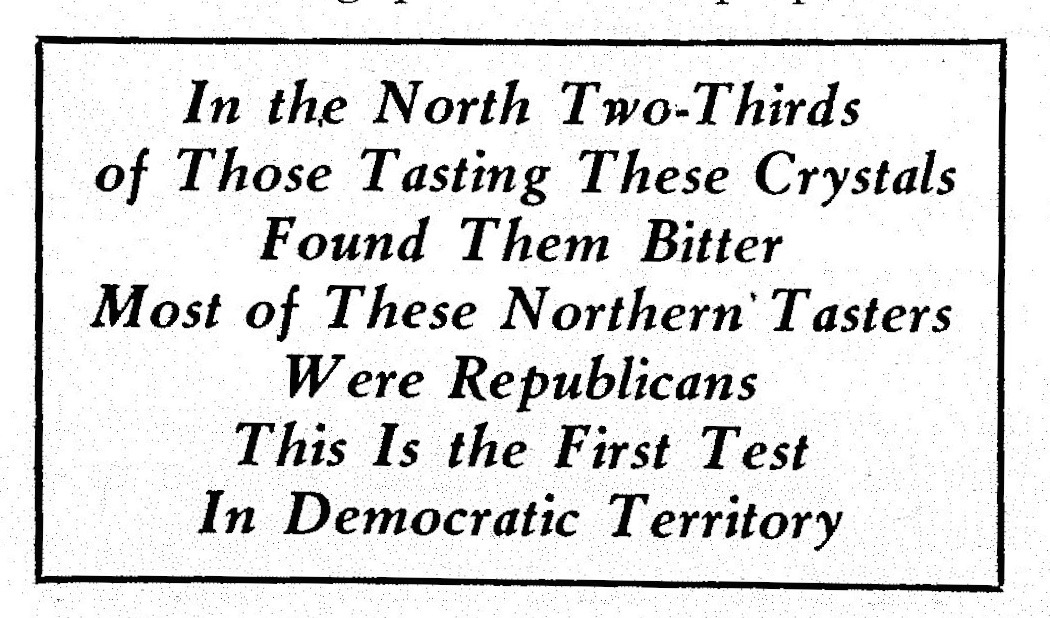

The AAAS exhibit in New Orleans even stoked regional, partisan sentiments in order to encourage participation:

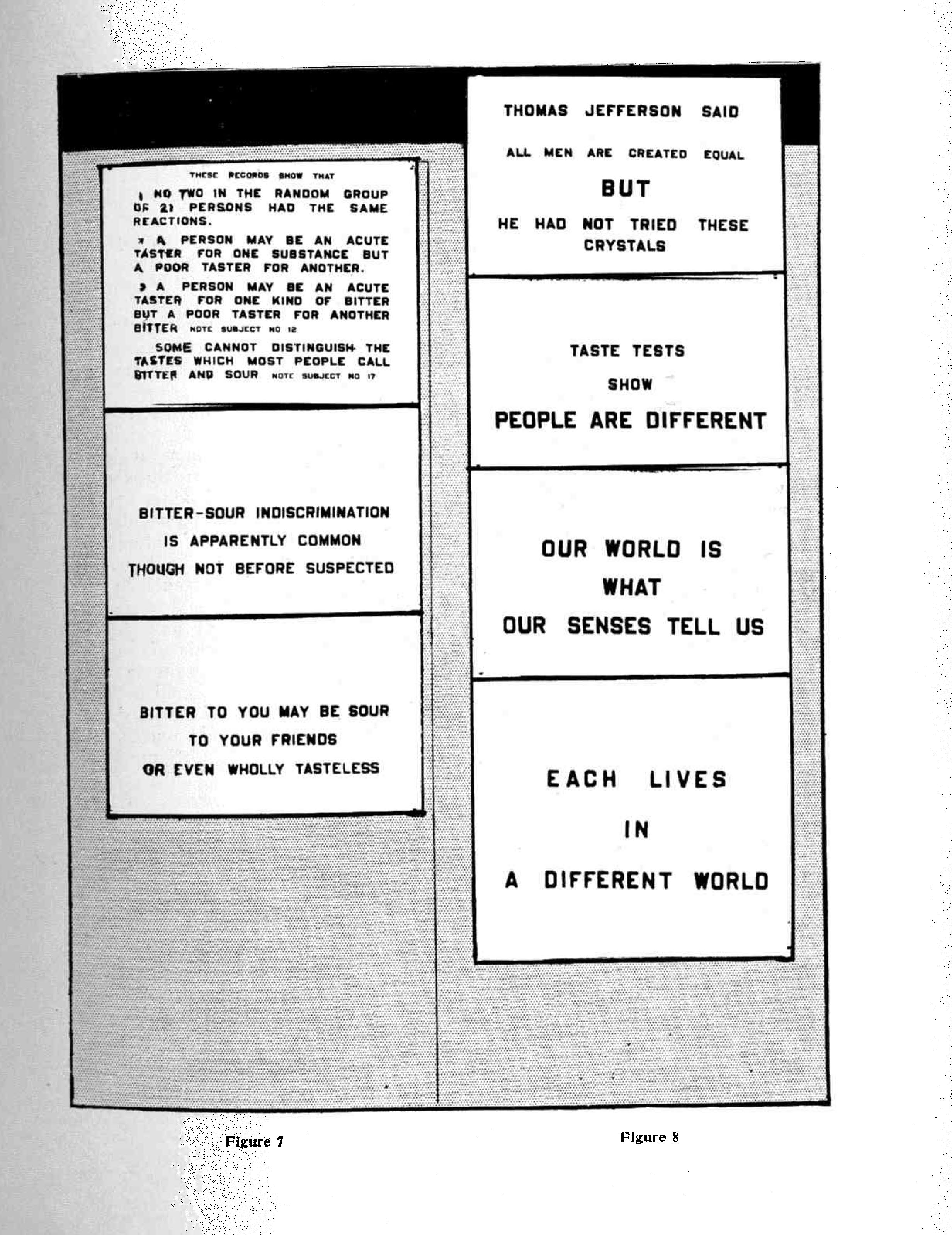

The voting machine was not only a tactic to lure visitors. It was a crucial part of the message the exhibit was meant to convey. After a series of charts illustrating the chemical structure of PTC and the inheritance of PTC taste acuity, visitors faced these posters, the culminating moral of the exhibit:

THOMAS JEFFERSON SAID ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL BUT HE HAD NOT TRIED THESE CRYSTALS

TASTE TESTS SHOW PEOPLE ARE DIFFERENT

OUR WORLD IS WHAT OUR SENSES TELL US

EACH LIVES IN A DIFFERENT WORLD

Differences in the perception of PTC were thus always standing in for other, fundamental differences among individuals. Differences that were innate, inherited, ineradicable, and profoundly meaningful.

The power of PTC lay in the immediacy and certainty of sensory response to the chemical. Tasters had a hard time accepting that non-tasters could not sense what they experienced as pungent bitterness. Non-tasters, likewise, were incredulous at the intensity tasters claimed to experience. (One non-taster man apparently berated his taster wife for making "a fuss over nothing.") According to Blakeslee and Fox, who wrote about the exhibit in the March 1932 Journal of Heredity (where these pictures are from), "a wide dissemination of this test might increase the realization that those who fail to agree with us may be as honest and faithful to the truth as ourselves, but that the picture their senses bring them may be as different from those that we perceive as black is from white."

The ultimate lesson here was not exactly supposed to be tolerance for other viewpoints. The public realization of this innate, ineradicable, irreconcilable difference in people's experience of the world, the authors dared to hope, would lead to a radical transformation of social, political, and cultural institutions, even a transvaluation of the values fundamental to American Democracy itself. According to Blakeslee and Fox, "much of our educational system and of our other efforts at human betterment are based on the tacit assumption that people are essentially equal in their innate capacities." The authors hoped that the evidence of different reactions to PTC would convince visitors that this assumption was wrong, and that they would draw certain conclusions from this realization. If the democratic institution of voting could not resolve the question of the "real" taste of PTC — "matters of personal sensation could not be decided by majority vote" — what other controversies could voting not resolve? The strong implication was that mass democracy was not a reliable way of adjudicating other matters, including the shape of laws, the distribution of resources, and the design of social institutions.

"Thomas Jefferson Said All Men Are Created Equal But He Had Not Tried These Crystals." E Pluribus Unum? No. We Live In Different (Taste) Worlds. "It is our belief that a full realization of the extent of differences between individuals would revolutionize the philosophy of 'the man in the street," Blakeslee and Fox wrote, "and through his philosophy would also affect his laws, religion, and other efforts at social advance."

Blakeslee developed this idea further in a lengthy speech published in Science ("The Genetic View-Point," May 29, 1931). He explained that the pillars of modern civilization — the educational system, professional norms, mass media — pushed young people toward uniformity, conformity, and standardization. He worried that mass democracy and mass culture were "spoiling interesting experiments in different parts of the world in customs and ways of thinking." He pleaded that children be protected from the forces of uniformity, from regression toward the mean, and that more attention should be devoted to "discovering and developing exceptional talent." The Declaration of Independence, with its assertion that all men were created equal? "This proposition, like many others assumed to be self-evident, is certainly not true," Blakeslee thundered. "Whatever politicians and others may say about the equality of mankind, the success of democracy is due to inequality, to leaders whom the majority learn to follow."

Unstated, but strongly implied, was that scientists and technicians would number prominently among these leaders — experts and authorities like Blakeslee himself who could steer the ship of state, adjudicate among the different worlds that we all live in, and properly direct the fate of mankind.

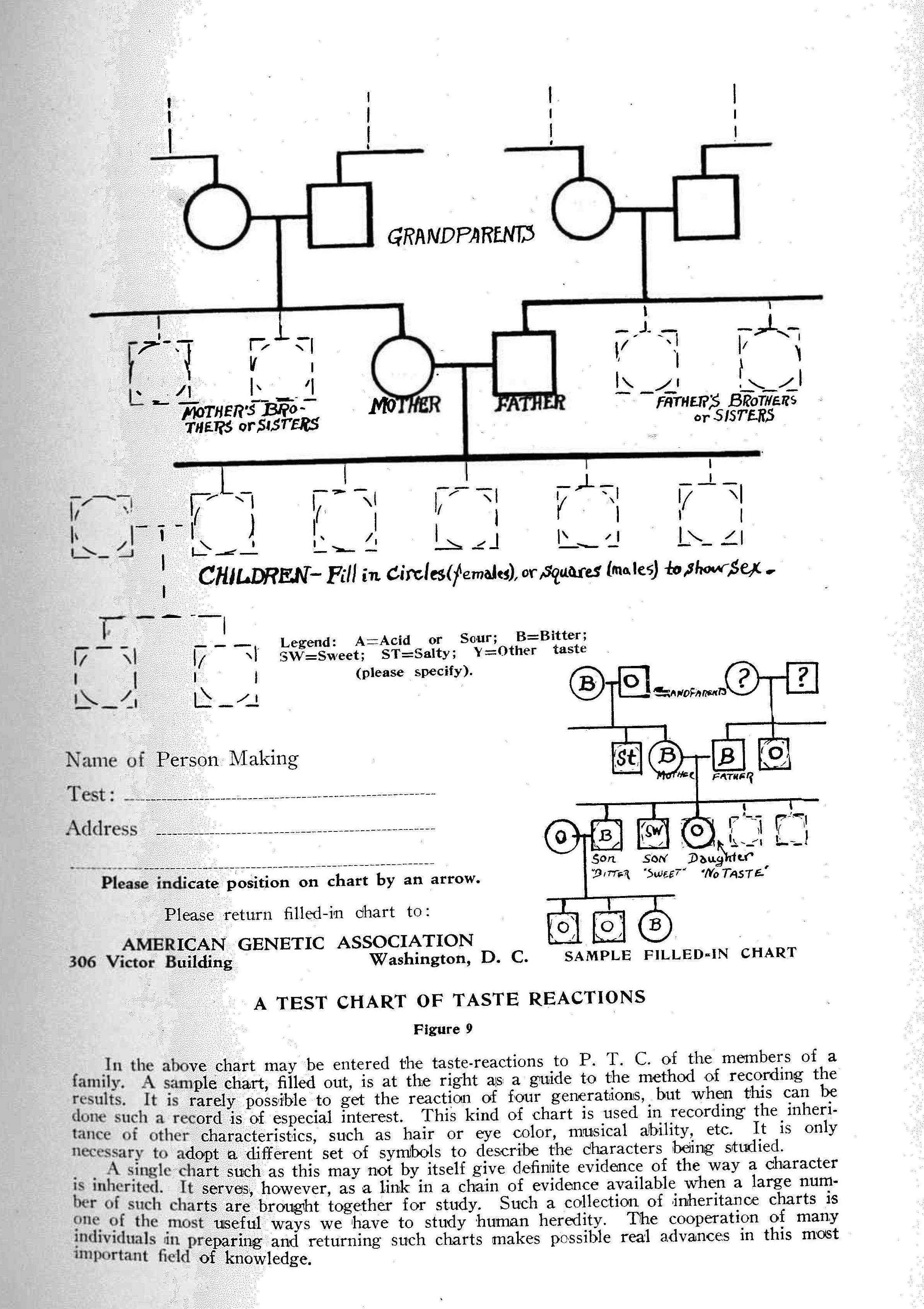

Blakeslee and Fox's 1932 Journal of Heredity article ended with an invitation to use the PTC taste-test as an educational tool in schools and colleges. Interested readers would find an envelope with PTC-impregnated paper test strips in the journal, as well as a blank heredity chart that students could use to map the inheritance of PTC-sensitivity in their own families. The American Genetic Association was prepared to furnish more PTC paper for classroom use at a "nominal charge." They had already mailed out more than 5,000 PTC test strips and blank heredity charts to interested educators for use in classes and clubs. "No other demonstration of heredity," the authors wrote, "has been so promptly and so enthusiastically adopted." By taking the test and filling in the heredity charts, huge numbers of non-scientists would be "actually engaging in research in human genetics."

"The cooperation of many individuals in preparing and returning such charts makes possible real advances in this most important field of knowledge."

The PTC taste-test was a way to recruit individuals to become willing participants in genetic studies of populations. It also meant to enlist them in new ways of thinking about themselves and others. Whether PTC tasted bitter to you or not had little apparent bearing on your life chances; it didn't even seem to have much correlation with your acuity in tasting and smelling other substances. But, as Blakeslee and Fox wrote, "if it were possible to bridge the gap between this character [ie, PTC sensitivity], which has no particular 'practical value,' and the growing list of others, of the utmost importance to the individual or to society, in which the same principles of heredity are operative, the value of the test will be still further enhanced." The alleged insignificance of PTC, its apparent harmlessness, opened the door to other kinds of tests, other kinds of conclusions.

Or did it? Ultimately, the messages that visitors and students took away from their experience with PTC did not necessarily conform to the lessons that the investigators so wanted to instill in them. Reflecting on the Taste Exhibition almost 15 years later, in a March 1945 article in The Biology Teacher ("Teachers Talk Too Much: A Taste Demonstration vs. A Talk About It"), Blakeslee admitted that all the detailed charts showing the inheritance of taste capacities, and the "charts which pointed out the moral which the taste tests were believed to show" — nobody read them. (Ruefully, he wrote: "The considerable labor involved in making these charts... could have been profitably avoided.")

Instead, what drew people to the exhibit was the noisy, clattering voting machine, and what kept them there was the surprise of sensation itself, tasting with others, discussing and disputing and marveling at the differences in their experiences.

Blakeslee shared another PTC story in his 1945 article in the The Biology Teacher. After his term at Cold Spring Harbor, Blakeslee taught botany at Smith. He tried out the PTC taste-test and his set of associated moral lessons in a speech to 2,000 students at the Smith College Assembly about "The Differences Between People, and the Significance of These Differences in Education and Other Human Relations." Surveying reactions afterwards, he found that what he said "was quickly forgotten, but this was not true about the taste of PTC." Two years after, students continued know him as the professor who gave them "awful-tasting stuff in assembly that some of the girls couldn't taste at all." But none of the students remembered anything he said about the importance of individuality in college education, nor his impassioned declaration that "college should be a weaner and not a feeder," nor did they retain any of his platitudes, such as "to learn to dispense with professors should be the aim of higher education."

All the Smith students seemed to remember was the bitter taste, or the lack of it — the vivid, certain reality of their own sensations, and how surprising it was to find that their classmates did not necessarily share it.

"The results of this assembly talk," he wrote, "though extremely unflattering to me, emphasize the value of the student's own experience over mere talk about it." He used this to argue for the importance of giving students more time to mess around in laboratories, to learn by doing and sensing, rather than passively listening to lectures or watching demonstrations. And he suggested a better way to use PTC as a teaching device. Instead of serving up the lessons of PTC sermon-style, he wrote, "it is possible that profitable use could be made of such a taste demonstration... in which the student could point the morals to be drawn in different fields of human activities."

Despite the apparent failure of his pedagogical efforts with the chemical, Blakeslee had not given up on his conviction that PTC was the right tool to experimentally prove the truth of his political ideology, the irreducible primacy of the individual and the impossibility of the collective. He left readers of The Biology Teacher with these parting words: "We believe that a few pounds [of PTC]... would be of more value to students than an equal number of tons of the usual run of didactic text books." Writing as the Second World War drew to a close, with the Cold War on the horizon, this seemed to him more important than ever.