The NuGrape Twins' recorded output is tiny: four songs in praise of the Lord, two in praise of NuGrape.

Like NuGrape, the twins are from Georgia. According to the Internet, their names were Mark and Matthew Little, born 1888, in Tennille, sort of in the middle of the state. NuGrape incorporated in Atlanta in 1921. Matthew and Mark Little apparently died in the 1960s, but you can still find NuGrape in stores.

The NuGrape Twins' "I've Got Your Ice-Cold NuGrape" (the B-side of "There's a City Built of Mansions") was listed in this catalog. 75 cents.

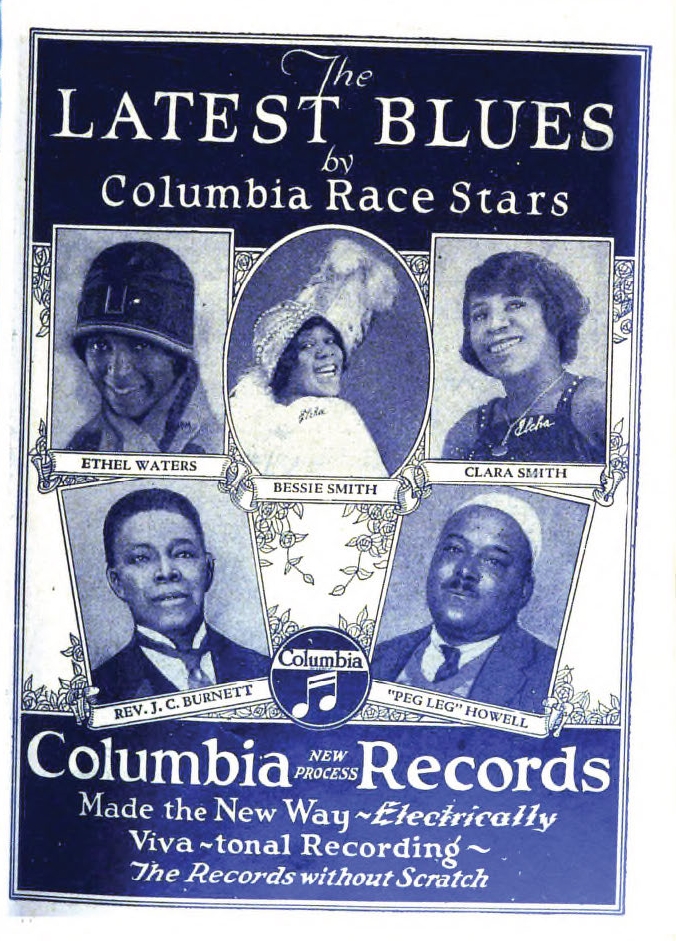

The exact nature of their twin-ship is obscure and probably lost to history (identical? fraternal? spiritual? promotional ploy?), but their voices are quite distinct. In "I've Got Your Ice-Cold NuGrape," listed in a 1926 catalog of "the latest blues by Columbia Race Stars," one twin sings in a tinny, determined countertenor, which, at moments, thins to wispiness; the other provides a shuffling baritone accompaniment, sometimes lagging a beat behind:

I got a NuGrape nice and fine

Three rings around the bottle is a-genuine

I got your ice-cold Nugrape

I got a NuGrape nice and fine

Got plenty imitation but there's none like mine

I got your ice-cold NuGrape

NuGrape may (or may not) be imitation grape, but that doesn't mean that NuGrape doesn't have a valor, and identity, of its own — that it doesn't have its own pretenders and imitators. There are a-genuine grapes, and there is a-genuine NuGrape.

Of course it would take twins to sing a hymn to NuGrape, grape's arcane twin. The relationship of NuGrape to "actual" grape is in a certain sense staged by the twins' performance. Just as their voices pass in and out of phase, harmonize, joining together in the wordless, hummed refrain, so NuGrape passes now closer, now further, from grape.

For these unsanctioned claims of kinship with actual grapes, NuGrape came under regulatory scrutiny twice in the 1920s.

The first time was in 1925. The Federal Trade Commission, which prosecuted violations of the Pure Food & Drug Act that had to do with misleading marketing, alleged that NuGrape deceptively represented itself as made from grapes and falsely claimed that its flavor came from grapes.

The FTC trotted out evidence of NuGrape's deceptive practices, including things like the cluster of grapes that were embossed on glass NuGrape bottles, and various slogans and images from advertising campaigns. (Note to fellow historians of these matters: FTC rulings are full of great information, such as sales data, manufacturing information, and advertising.) Here are some of the advertising slogans:

"NuGrape is made from the purest of pure Concord grapes"

"NuGrape has a way about it — makes you forget the heat and humidity, and remember only those luxuriant days when Concord grapes ripen on the vine and all the air is honey-sweet"

"It's just that sort of flavor, a mysterious something, born of plump Concord grapes and sunshine"

"NuGrape is as full o'Health as the rich, full-flavored joy of the grapes from which it is made"

"It is in no sense 'just a grape drink.' It is more"

Government chemists determined that a bottle of NuGrape was, in fact, both more and less than a "just a grape drink." It contained less than two percent grape juice; the rest was sugar syrup and carbonated water. What small fraction of grape juice it did contain was not enough to give the beverage "its characteristic flavor." "Said flavor," the chemists concluded, "is due principally to other and artificial sources." Flavor additives that NuGrape was required to, but had failed to, disclose.

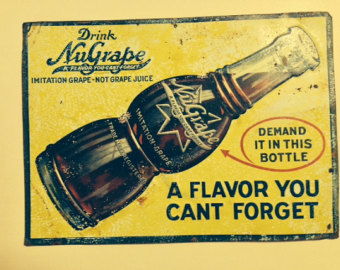

On these grounds, the FTC ordered NuGrape to cease and desist using images of grapes or grape vineyards in its advertising or marketing material, and to emblazon on all NuGrape labels, caps, and advertisements with the confession: "Imitation grape — not grape juice."

For several years, NuGrape complied. But by the time the NuGrape came to the FTC's attention again, in 1929, the company had stopped doing this.

NuGrape had changed its formula. Fritzsche Brothers, a flavoring and fragrance company then located in Brooklyn, had started supplying NuGrape with something called "Merchandise No. 25" also known as "Fritsboro True Grape Aromatics, New Process."

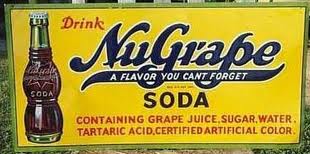

This "true grape" flavoring, Fritzsche claimed, was derived entirely from grapes; it was not an imitation. Accordingly, NuGrape changed its label. It no longer admitted that it was "imitation grape -- not grape juice," but instead explained itself this way: "artificial color NUGRAPE SODA, containing in addition to grape juice, simple sirup, tartaric acid, and water."

NuGrape: containing grape juice, sugar, water, tartaric acid, certified artificial color. This dates from after the addition of Fritzsche's Merchandise No. 25, but before the 1931 FTC ruling requiring the company to reinstate "imitation" on their labels.

But what exactly was "Merchandise No. 25"? Government agents needed to know.

Fritzsche Brothers explained that they started with a vacuum-concentrated grape juice shipped to Brooklyn from California. To bring this 4:1 concentrate to the 8:1 strength they needed, they added "aromatic grape concentrate made from grapes by our own secret process." The aromatic grape concentrate used Concord grapes (foxy with methyl anthranilate), but beyond that, the company would say no more. A production specialist at Fritzsche "refused to give any further information about their so-called secret process on the ground that it would be disclosing trade secrets," and so chemists at the FDA (then the Food, Drug & Insecticide Bureau) investigated Merchandise No. 25.

They found that the flavor of NuGrape syrup"is derived chiefly from added tartaric acid." Tartaric acid is "not found as such in grapes or grape juices." It is "obtained from crude argols, commonly called wine lees, by-products, or precipitates, obtained in the treatment of grape juice or the manufacture of wine." In other words, there is a way that you could reasonably claim that tartaric acid is made from grapes.

(If you've got a container of cream of tartar stuffed in the back of your cupboard somewhere, it might just have an image of a barrel on it. That's a wine barrel, a now almost inscrutable gesture toward the substance's origins.)

In the eyes of regulators, however, there was too much distance between grapes and tartaric acid; what was grape about the grape had been transubstantiated, turned into a chemical. NuGrape's label already disclosed that tartaric acid had been added to the beverage. However, that was not sufficient. NuGrape, artificially colored, flavored with materials once derived from grapes but grapes no longer, was in the eyes of the law an imitation. The FTC's ruling, handed down in 1931, required the company to change their labeling and marketing to reflect that the product "is an imitation, artificially colored and flavored."

What underlies this chemical judgment is a value judgment: that the flavoring chemical was made, essentially, from garbage — from the wastes of other industries. Although it dates from a decade later, this October 29, 1941 letter from P.B. Dunbar, assistant commissioner of Food & Drugs, to the chief of the central regulatory district, substantially reflects the agency's attitude and policy toward flavoring additives:

"Heretofore on products of vague identity offered to food manufacturers we have felt that the requirement for the labeling of the ingredients by their most informative names was a means by which the buyer could determine the worth, if any, of these often glorified addition substances. In other words, the mere recitation that the product is a few cheap chemicals and water takes out all the mystery."

The "products of vague identity" are the flavor additives produced by flavor and fragrance companies. The FDA, by requiring flavor additive manufacturers to reveal their ingredients, wants to demystify these "glorified" and overvalued additives. For Dunbar and the agency, flavoring additives are not innovative products developed by skilled workers, but "a few cheap chemicals and water."

Underlying this is a more profound anxiety: that consumers won't be able to tell the difference between — for instance — grape and NuGrape unless "Imitation" is branded on the label. If there is a world of difference between the pastoral orchard and the chemical leached from the lees, then shouldn't that difference reveal itself at first sip? If the distinction between "real" and "fake" is somehow no longer self-evident, then what are the prospects for the continued persistence of the real?

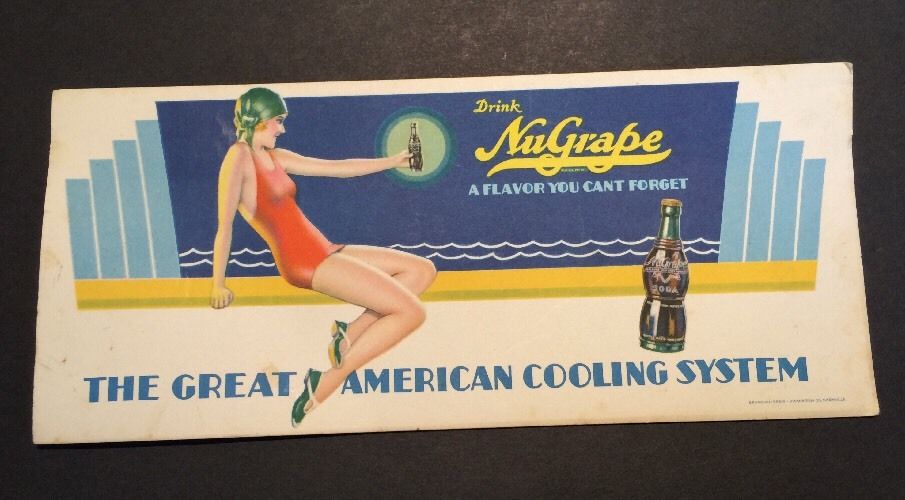

But is NuGrape best understood as an "imitation," as a cheaper substitute for actual grapes? Or is there a way that NuGrape can be genuine without being imitation? NuGrape's early advertising material claimed that the beverage could deliver the essence of the experience of grapes to the parched but orchard-less masses — to bring the pastoral within one's (mnemonic) grasp. Yet later promotions — including those intoned, probably without remuneration, by the NuGrape Twins — hint at other all the things that foods begin to be able to do in modernity.

One advertisement cited in the second FTC complaint was a poster featuring a tennis player grasping for a bottle of the drink. The slogan:

"When you were never so thirsty in your life! Reach for NuGrape"

NuGrape delivered genuine refreshment to the body depleted by leisure, not labor. A healthy, modern, exhausted tennis-playing body. And the flavor of NuGrape was attuned to the amplifications and new intensities of experience in modernity, new modes of being in the world. There were appetites, perhaps, that the orchard could no longer satisfy.

As the NuGrape Twins knew well, NuGrape was also a substance that could lift depressed spirits:

When you're feeling kinda blue

Do not know what's ailing you

Get a NuGrape from the store

Then you'll have the blues no more...

Or pacify the rage of a termagant wife:

If from work you come home late

Smile and 'prise her with NuGrape

Then you'll sneak through in good shape...

Or serve as a love-charm, a token of otherwise inexpressible ardor:

Sister Mary has a beau

Says he crazy loves her so

Buys a NuGrape every day

Know he's bound to win that way

As Burgin Mathews wrote of "I Got Your Ice-Cold NuGrape" (the Twins' "masterpiece") in the All Music Guide to the Blues, the song is "a simultaneous hymn and jingle that advertises the soda as a cure for any earthly or spiritual ailment."

To be clear, none of these things are necessarily more grandiose or remarkable than what foods could do to bodies in the early modern era, when food could treat and cure diseases, temper imbalanced humors, and recalibrate one's relationship with the actual cosmos.

In the final accounting, however, there is something heavenly about NuGrape.

"Is there no change of death in paradise?" asked Wallace Stevens. "Does ripe fruit never fall?" "Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens," according to the Talking Heads.

For NuGrape to become "the flavor you can't forget," it must conform itself not to the flavor of grapes hanging heavy on the bough, but to prior memories of NuGrape. To the bodily, social, and spiritual array of pleasures, comforts, and gratifications that affiliate themselves with the sensations that NuGrape provides. Like the unchanging fruits of heaven, NuGrape must always resemble itself.

All the way from Maine to the Gulf of Mexico

From the Atlantic to the calm Pacific shore

NuGrape is the best friend yet

So try a bottle of NuGrape

The flavor you can't forget