We don't tend to think of freshness as a flavor, at least not in the same way that we think of "orange" or "vanilla" as flavors. "Freshness" is supposed to indicate something about a thing's material condition, its temporality: its recentness to the world and to us. The life history of a fresh food is assumed to be reassuringly direct: there were few intermediaries, few machines intervening, as it made its way to us. Fresh foods are also by definition not stable -- nothing can be fresh forever -- and so always at risk of becoming not-fresh, stagnant, rotten, stale.

There's something uncanny about a fresh-seeming food that is really an old food -- like the changeless McDonald's hamburger in Supersize Me, or those legendary Twinkies from decades ago, still plump and gleaming in their wrappers -- something reflexively repulsive. It brings to mind succubus myths, old women who make themselves appear young and nubile to seduce enchanted knights. Those stories certainly deserve some full-strength feminist revisionizing, yet remain among the purest expressions of the grotesque in our culture.

At the turn of the 20th century, one of progressive reformers' most potent accusations against food manufacturers was that they hired chemists to rehabilitate and deodorize rotten meat and rancid butter, to restore them to the appearance of freshness. This is a deceptive practice -- akin to running back the odometer on a used car -- but pure food advocates also largely opposed chemical preservatives, which didn't run back the meter so much as slow its rate of progress. Part of their opposition came from the claim that these chemical additives were harmful, but I think some of the horror of it was that preservatives made the question of freshness beside the point. Some foods were fraudulent by passing themselves off as something they weren't: margarine for butter, glucose for maple syrup. What chemical preservatives were doing was faking freshness.

The problem isn't so much that the food is rotten or dangerous, but that you can't tell the difference between fresh and not-fresh, and that difference matters to us. Time changes food; and food unchanged by time seems somehow removed from the natural world, indigestible.

Yet why does freshness matter so much? (We don't always favor new-to-the-world foods, of course. Sometimes time increases value: think of old wines, caves of teeming cheeses, dry-aged beef, century eggs).

What we call freshness is not an inherent condition of a food, but an interpretive effect. We read it from cues including color, taste, aroma, texture, as well as the contexts of consumption. This is what I'm arguing here: freshness is a cultural or social category, not a natural one.

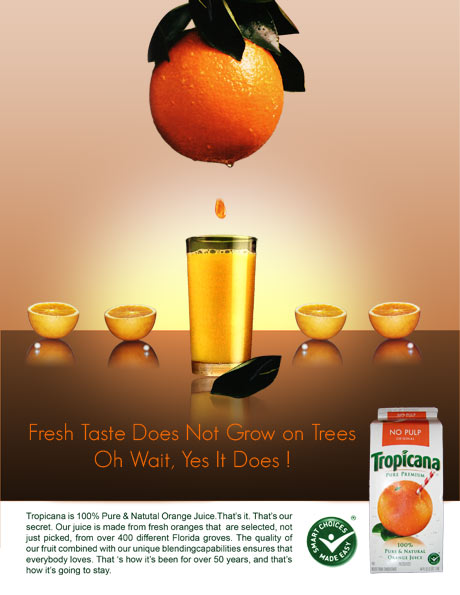

As a case in point, consider the story of store-bought "fresh-squeezed Orange Juice," as described in the April 2014 Cook's Illustrated feature somewhat luridly titled:

The Truth About Orange Juice

Is the sunny image of our favorite breakfast juice actually just pulp fiction?

Cook's Illustrated -- one of my all-time favorite magazines, by the way -- assembled a panel of tasters to evaluate various brands of supermarket orange juice. With the exception of two low-cal samples, all the juices list only one ingredient on the label -- orange juice.

Nonetheless, as Hannah Crowley, the article's author, extensively illustrates, orange juice is a processed food: blended from different oranges, pasteurized, packaged, shipped across continents or over oceans, and required to remain shelf-stable and "fresh tasting," at least until its expiration date. Orange season in the US lasts three months. But we want orange juice all year long.

Part of the challenge of producing commercial name-brand OJ is consistency. How do you get each container of Minute Maid to taste the same as every other container, everywhere in the world, in May or in October? Coca-Cola, the corporate parent of Minute Maid and Simply Orange, uses a set of algorithms known as "Black Book" to monitor and manage production. As an article last year in Bloomberg Businessweek put it: "juice production is full of variables, from weather to regional consumer preference, and Coke is trying to manage each from grove to glass." In all, Black Book crunches more than "one quintillion" variables to "consistently deliver the optimal blend," the system's author told Bloomberg, "despite the whims of Mother Nature."

Sure, but how do you reproduce the experience of freshness? Preservation is not enough. In fact, the means used by OJ producers to arrest decay and rancidity in order to allow them to "consistently deliver" that optimal blend -- pasteurization and deaeration -- actually alter the chemical profile of the juice, in ways that makes it taste less fresh. Pasteurization can produce a kind of "cooked" flavor; deaeration (which removes oxygen) also removes flavor compounds.

Freshness is an effect that is deliberately produced by professional "blend technicians," who monitor each batch, balance sweetness and acidity, and add "flavor packs" to create the desired flavor profile in the finished juice. Flavor packs are described by Cook's Illustrated as "highly engineered additives... made from essential orange flavor volatiles that have been harvested from the fruit and its skin and then chemically reassembled by scientists at leading fragrance companies: Givaudan, Firmenich, and International Flavors and Fragrances, which make perfume for the likes of Dior, Justin Bieber, and Taylor Swift." The only ingredient on the label of orange juice is orange juice, because the chemicals in flavor packs are derived from oranges and nothing but oranges. Yet orange juice production also has something to do with the same bodies of knowledge and labor that made "Wonderstruck" by Taylor Swift possible. (There are in fact multiple class-action suits alleging that the all-natural claim on orange juice labels is inaccurate and misleading.)

In other words, this isn't just about "adding back" what has been unfortunately but inevitably lost in processing, restoring the missing parts to once again make the whole. The vats of OJ, in a sense, become the occasion for the orchestration of new kinds of orange juice flavors, that conform not to what is common or typical in "natural fresh-squeezed orange juice" (whatever that may be), but to what we imagine or desire when we think about freshness and orange juice. As Cook's Illustrated puts it: "what we learned is that the makers of our top-ranking juices did a better job of figuring out and executing the exact flavor profile that consumers wanted." These flavors don't reproduce nature; they reproduce our desires. But how do consumers know what they want, exactly, and how do manufacturers figure out what this is?

I can't really answer either of those questions now, but I think one of the consequences is a kind of intensification of the flavor dimension of things. Consider: consumers in different places want different things when it comes to OJ. Consumers the US, according to Cook's Illustrated, especially value the flavor of freshness. One of the volatile compounds present in fresh orange juice is ethyl butyrate, a highly volatile compound that evaporates rapidly and thus is correlated with the newness of the OJ to the world, so to speak. Simply Orange, Minute Maid, and Florida's Natural juices -- all juices "recommended" by the Cook's Illustrated tasting panel -- contained between 3.22 and 4.92 mg/liter of ethyl butyrate. But juice that's actually been squeezed at this moment from a heap of oranges contains about 1.19 mg/l of ethyl butyrate. The equation here is not as simple as ethyl butyrate = fresh flavor, so more ethyl butyrate = megafresh flavor. (One of the exception on the panel's recommendations - an OJ with an ethyl butyrate content more in line with that of fresh-squeezed juice - was actually produced in a way that permitted seasonal variations, was not deaerated, had a much shorter shelf life, and depended on overnight shipping to make its way to stores.) But there is a kind of ramping up, somehow, that seems to both correlate with our desires and recalibrate them.