The autumn air smells faintly like lollipops.

It's late November, and I’m passing through the main gates of Bell Flavors & Fragrances’ European headquarters in Miltitz, just outside of Leipzig, on my way to visit the Schimmel Library, possibly the largest collection of flavor- and fragrance-related books in the world. I walk sniffing the air, bunny-like, trying to pin names on spectral fruits. But the atmosphere keeps changing. I catch a whiff of something sharp and sulfurous, like the burnt residue at the bottom of an office coffeepot crossed over by a skunk. When I sniff again, it’s gone, and there’s only a faint earthy odor, a mushroom’s dank gills – impossible to say whether it emanates from ground beneath the row of ashen birch trees, sopped with the morning’s drizzle, or from the low white building behind them, blank and garlanded with HVAC ducts. I keep walking. The molecules in the air continue to rearrange themselves. As I push in the ornate wooden doors of the building that houses the library, I once again inhale only fruitiness.

Schimmel Library front desk, with librarian Ricarda Bergmann, a real star. The inscription above her head reads: "Among these books sat scientists, scholars and Nobel prize chemists dedicated to discovering the mysteries of nature as it relates to essential oils, flavors, fragrances, and aroma chemicals. To the pioneers of the future who follow in their footsteps those of the past send their greetings."

This land, and the library I am visiting, once belonged to Schimmel & Company, one of the first flavor and fragrance companies. Since purchasing Schimmel in 1993, Bell has restored the library, which had fallen into disuse and disrepair during the decades when Leipzig was part of the DDR (East Germany), and Schimmel was a state-owned enterprise. This is now a thoroughly modern flavor and fragrance manufacturing facility. The grounds are silent, the odors in the air are muted. In this little sketch about my visit to the Schimmel Library last month, I want to raise some of the ghosts of the past, paint a picture of what it was like to make flavors and fragrances in Miltitz in the years immediately before the First World War.

The company that would become Schimmel & Co. was founded in Leipzig in 1829 as Spähn and Buttner, a drug-maker at a time when many medicines were derived from botanical materials. The company quickly passed through several owners and name changes, but by the 1870s, it was known as Schimmel & Co. and was solely in the hands of the Fritzsche family. During this time, it shifted its focus from the manufacture of pharmaceuticals to the production of essential oils. Under the Fritzsches’ leadership, Schimmel & Co. grew rapidly, pioneering scientific analysis and production methods. The company established the first research laboratory in the essential oil business, and incorporated several foreign branches, including Fritzsche Brothers in New York, to manufacture and distribute its products globally.

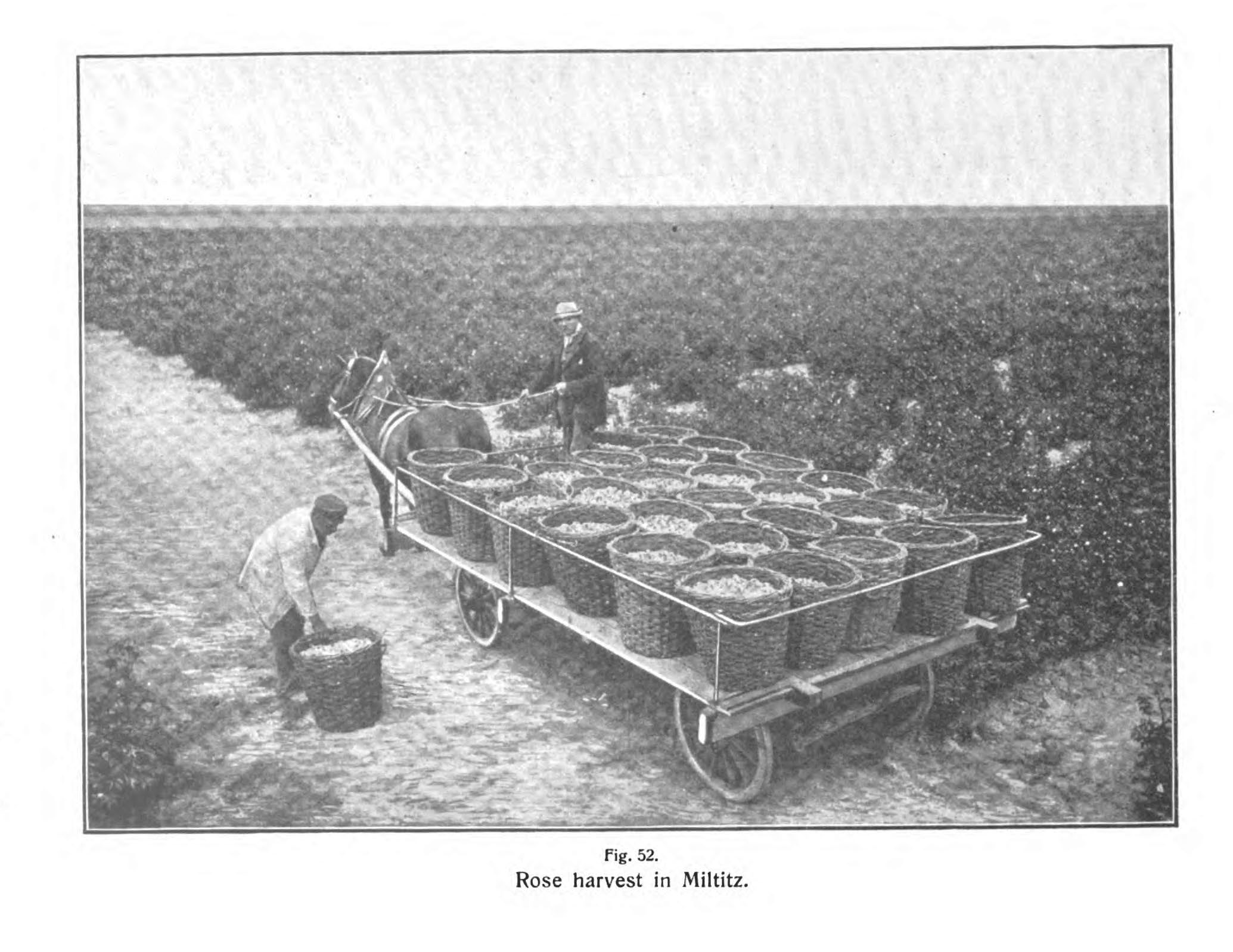

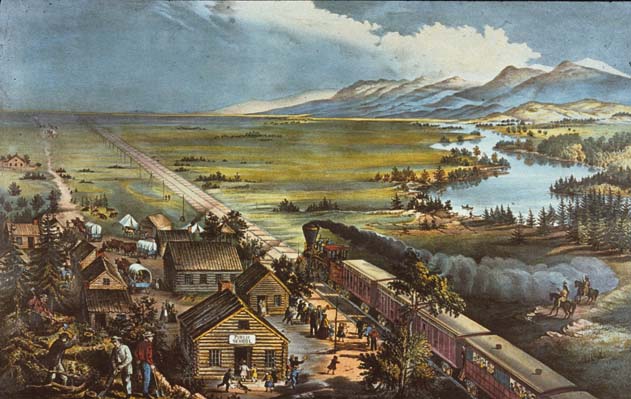

In the early 1880s, Schimmel began manufacturing its own rose oil in mass quantities, supplementing and improving upon traditional sources in Bulgaria. Rose petals are fragile, and must be processed as soon as possible after harvest to retain their evanescent fragrances, with gentler steam rather than high heat. The company purchased dozens of acres of land in Miltitz, a town about six miles west of Leipzig, on the path of the Thuringian railroad. There, it cultivated German and Bulgarian roses in tidy, thorny rows. "It goes without saying that here the crudities of the Bulgarian process are not tolerated," wrote Edward Gildemeister, Schimmel chemist, in his description of the company's methods in his foundational 1899 monograph on essential oil chemistry. "Owing to the greater care exercised, the odor of the German oil is far superior to that of the Bulgarian."

Harvesting rose petals to make rose oil in Miltitz. From The Volatile Oils, the english translation of Gildemeister and Hoffmann's Die Aetherischen Oele, the first scientific monograph on essential oil chemistry, first published in 1899. Gildemeister was a chemist at Schimmel & Co., and much of the information included in the book was based on research conducted at the company.

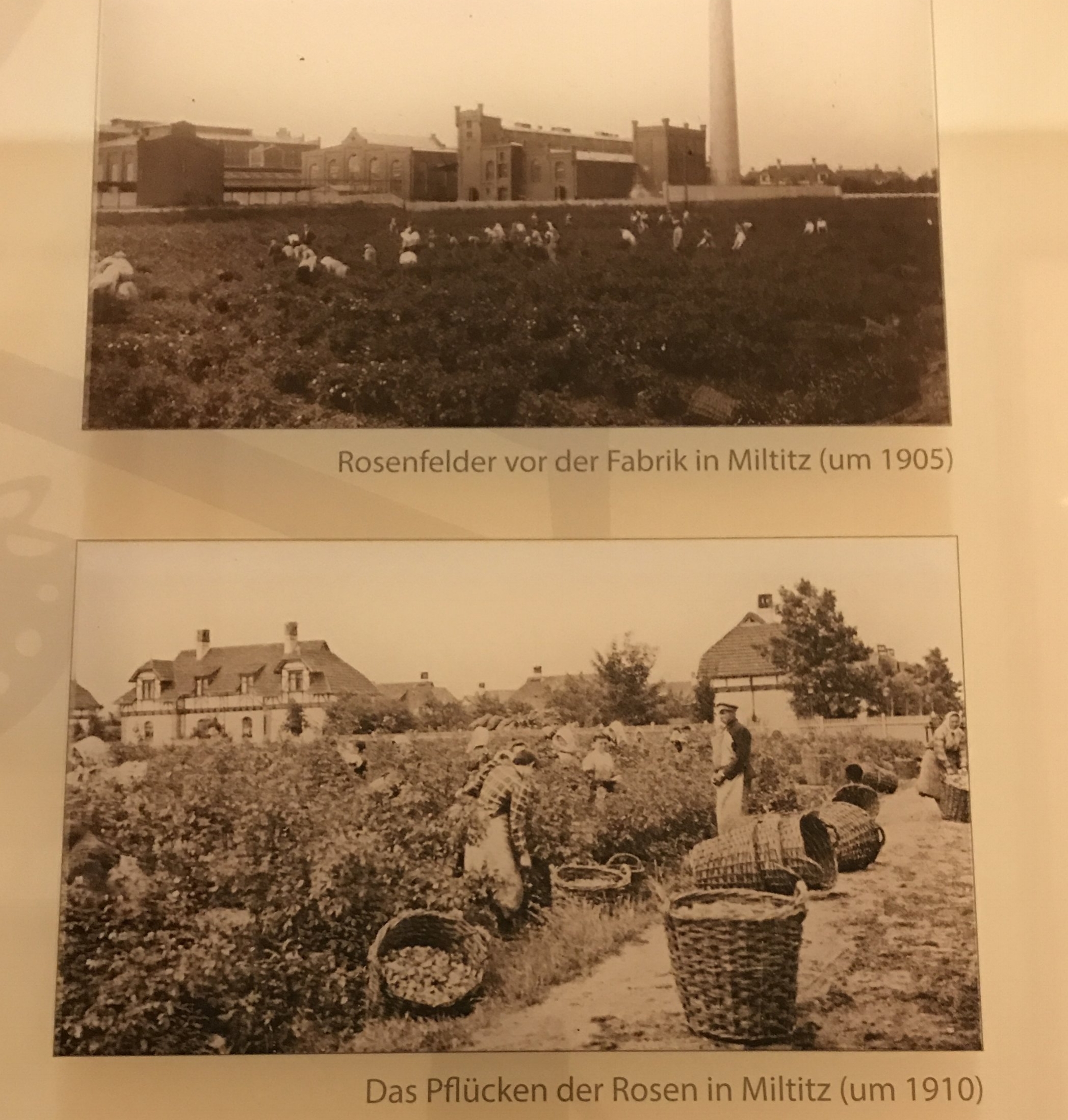

Images of rose fields and rose field workers, from the small exhibit of the company's history displayed in the atrium outside the Schimmel Library.

I don’t know how many people worked in those fields, plucking petals off roses in bloom, who they were, or what their labor was like. But this should suggest the scale of the project: one kilo of rose oil required five to six thousand kilograms of flowers. Roses were also quite fussy to cultivate. A cold night in early June 1911, when the temperature fell below freezing while the flowers were still in bud, destroyed that entire season’s crop.

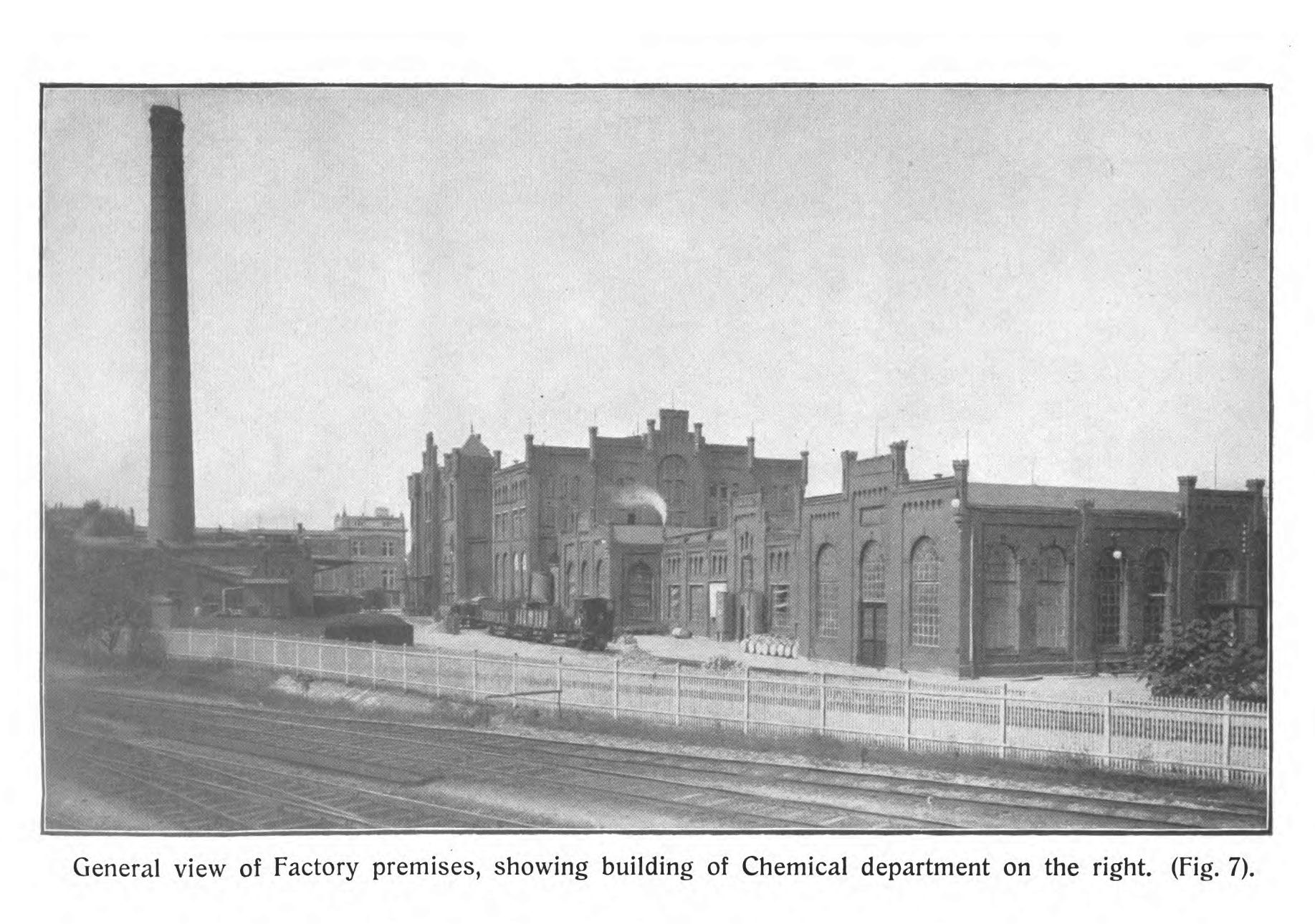

In 1900, Schimmel & Co. left Leipzig behind and relocated to Miltitz, raising a large complex of factories, workshops, and laboratories amidst its fields of roses. By the beginning of the First World War, Schimmel & Co. owned around 300 acres of land in the town. It had its own post office, power plant, printing shop, water purification system, and sewer network. It also built a model village for its workers and managers to live in, just across the street from the walls of the factory complex, surrounded by gardens and rose fields.

Zeppelin's-eye view of Schimmel & Co. in Miltitz, from the April 1914 Schimmel & Co. Semi-Annual Report. The twin smokestacks correspond to the two boiler-houses, which supplied steam for distillation to the complex. The model worker's village is to the right of the factory complex. the town of Miltitz lies behind the factory. Railcars on the Thuringian railway can be seen in the mid-left margin of the image, approaching or receding along a diagonal. Rose fields stretch across the foreground and border the worker's village.

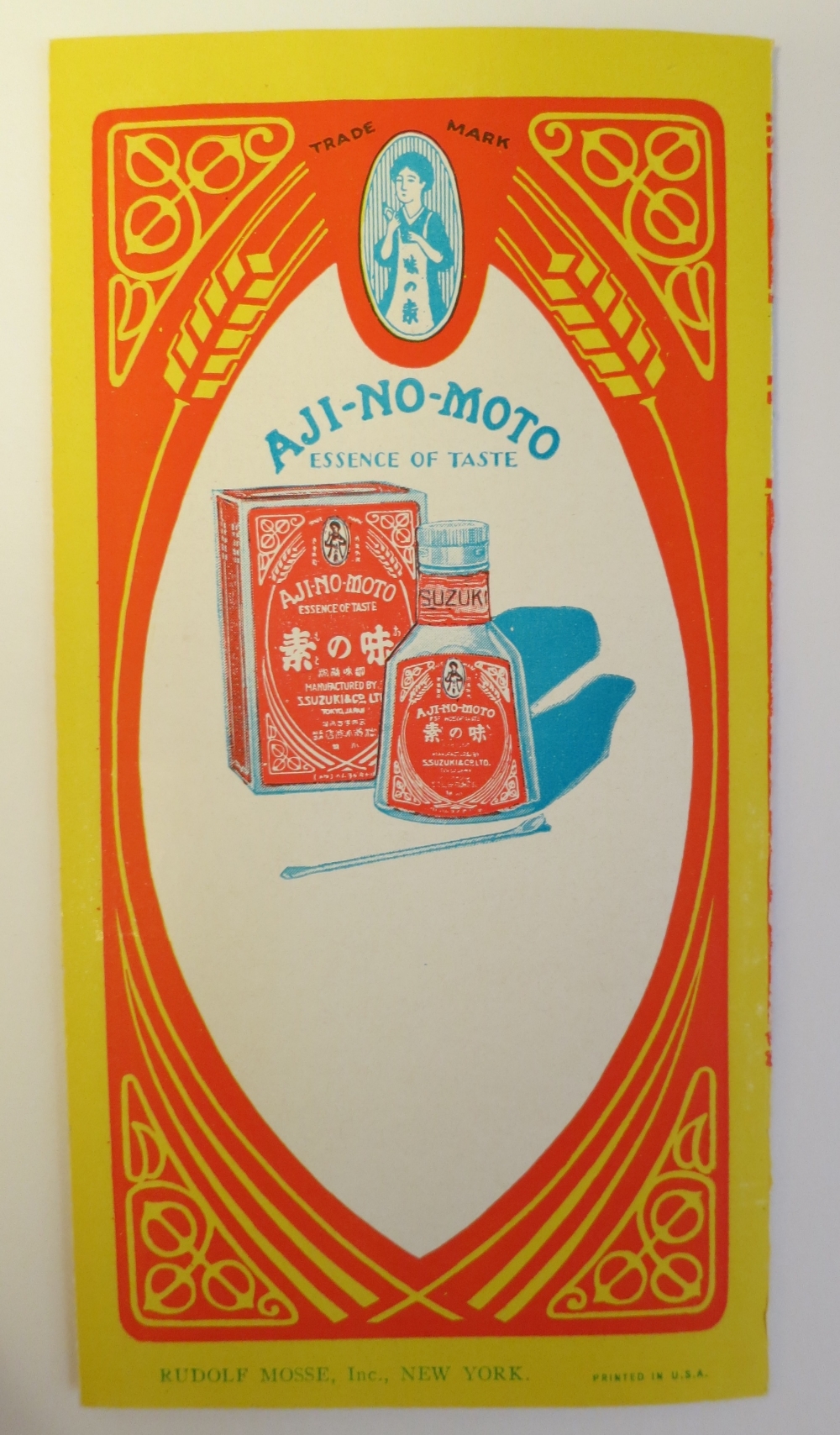

At this time, Miltitz, on the fringes of Leipzig, in the middle of Europe, on the cusp of the First World War, became a central collection and redistribution point for a world’s worth of fragrant, pungent, and aromatic stuff. In addition to the roses and other aromatic herbs cultivated in the surrounding area, the Schimmel factory processed hundreds of raw materials imported from foreign and colonial sources: sandalwood, patchouli, orris, and cedar; lavender, eucalyptus, and jasmine; animal musks and ajowan seeds; camphor and turpentine; ginger roots and caraway. (Ten tons of caraway seeds a day in 1908, according to one source.)

In Miltitz, these substances were reduced to their essences, analyzed, purified, concentrated, standardized, and packed into uniform bottles, ready to be incorporated into a diversifying range of consumer goods: perfumes, soaps, cosmetics, disinfectants, medicines, and flavorings for liqueurs, sodas, candies, and other manufactured foods. The mechanical and chemical processes perpetrated upon raw materials at Schimmel & Co. made a growing number of new sensations available to expanding circles of people. In some regards, this was a kind of democratization of luxury — the otto of roses that once perfumed the silks of a wealthy lady, now wafted from the handkerchief of the girl at the factory — but the effect was more than simply making rare things more common, or costly things cheap. What was made in Miltitz were the building blocks of a new sensual order, based in chemical technologies, which permitted sensations to be reimagined as discrete and manipulable molecular arrangements.

The French historian Alain Corbin has called the nineteenth century an era of deodorization. Cities had always stunk, with their concentration of bodies, animals, excrement, and garbage, but around the beginnings of the industrial revolution, people began minding the stench. Governments took up large-scale hygienic projects — subterranean sewers, water treatment facilities, slum clearance — and passed laws regulating insalubrious odors from workshops and factories, with the related goals of improving public health and minimizing obnoxious smells. (The relocation of Schimmel & Co.’s factory from Leipzig to its outskirts was likely part of this process, removing a smelly factory to a place where it might bother fewer people.) Meanwhile, personal habits and norms changed concerning bathing and cleanliness, body odors, underwear, and laundry.

The technological and cultural processes of “deodorization” didn’t leave behind odorless places and unscented bodies. The world that industrialization produced — both deliberately and incidentally — still smelled, just different. (I think Melanie Kiechle writes about this in her new book, The Smell Detectives.) You can think of it as a redistribution of the planet’s olfactory potentials. Certain kinds of aromas multiplied, attaching themselves to bodies, clothing, cleaning products, living spaces, public spaces, just as other odors were suppressed, scrubbed away, deemed offensive.

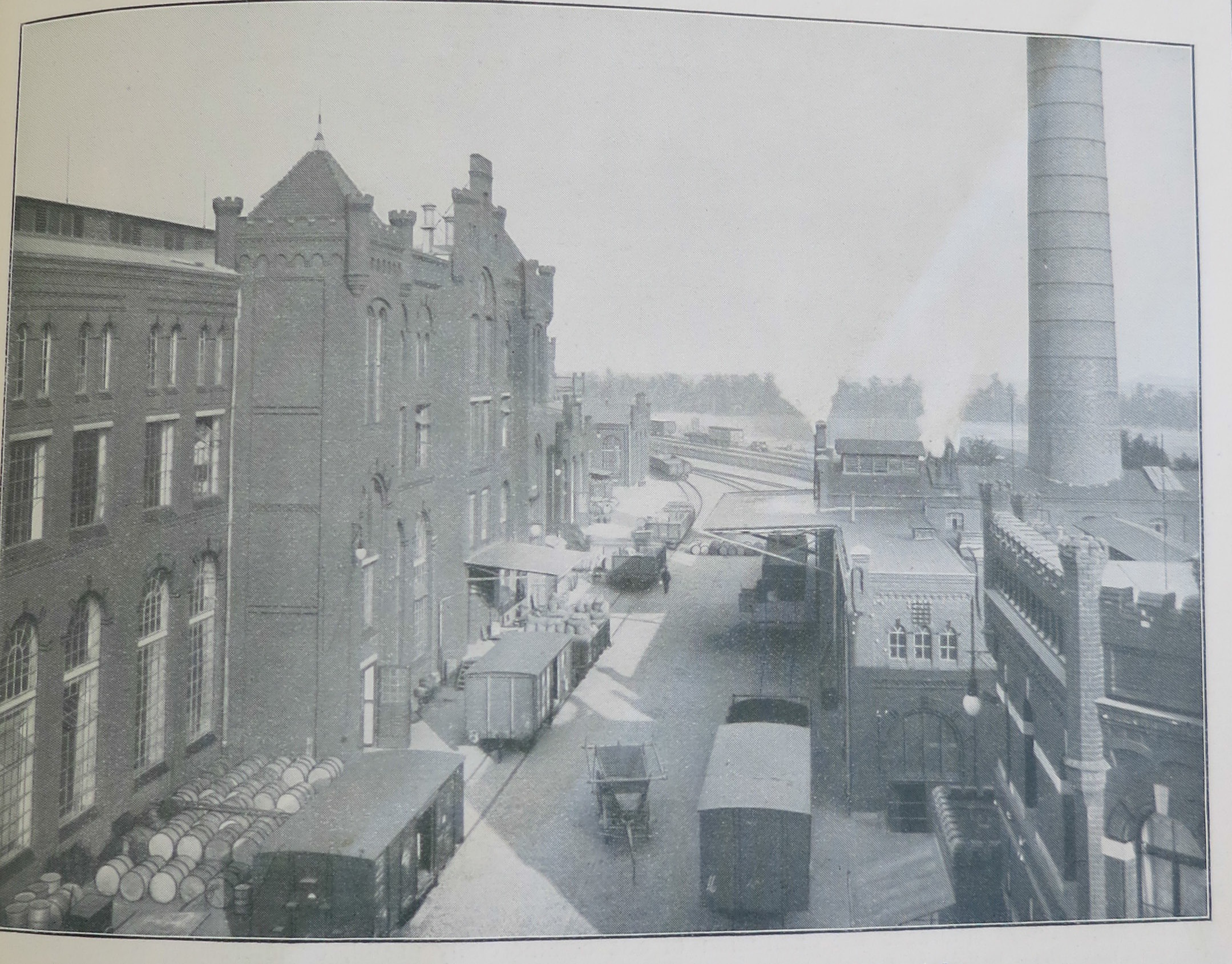

Schimmel & Co.’s business was at the center of this large-scale re-scenting of the industrial world. This enterprise required an immense concentration of raw material, energy, resources, and labor. In 1912, the factory employed more than 100 clerks, around 250 workmen, 16 analytic chemists, and 20 technicians. In 1908, the factory used about 880,000 gallons of water a day, comparable to a town of 50,000 people. In 1912, it burned through 45,000 tons of coal. Industrial waste and sewage was carried away by pipes “to distant irrigation fields, covering some 7 acres.”

From Schimmel & Co.'s Works, 1908.

There are two detailed English-language descriptions of Schimmel & Co.’s Miltitz works, published in 1908 and 1913, and the figures, quotes, and some of the historic images here come from those (I’ll include links to sources at the end, if you’re curious). Both make it clear that transforming blossoms, leaves, woods, seeds, resins, and other botanical stuff into essential oils and aromatic chemicals was a noisy, smelly, messy business.

The largest building in the complex was where essential oils were manufactured. Its second floor was filled with a variety of “disintegration machines,” each specially designed to reduce specific raw materials to the form from which their essence could be most effectively extracted. The pounding, sawing, crushing, and pulverizing machines was “deafening,” filling the air “with the incessant roar and screech of ceaseless, throbbing energy — a veritable symphony of modern labor.” Nets shrouded the room, to catch the dust.

Once “disintegrated,” raw materials funneled down through the floor to custom-built distillation stills on the ground level, where they were separated and concentrated under carefully controlled conditions of heat and pressure. “Here we are met by the hissing, the roar and the rush of the steam.” This was a vast space with 26-foot ceilings and huge arched windows that let in the light and vented out the odors and the heat. “An all-pervading cloud of mysterious and indefinable perfume permeates this great hall,” the thick confounding mixture of aromas from everywhere.

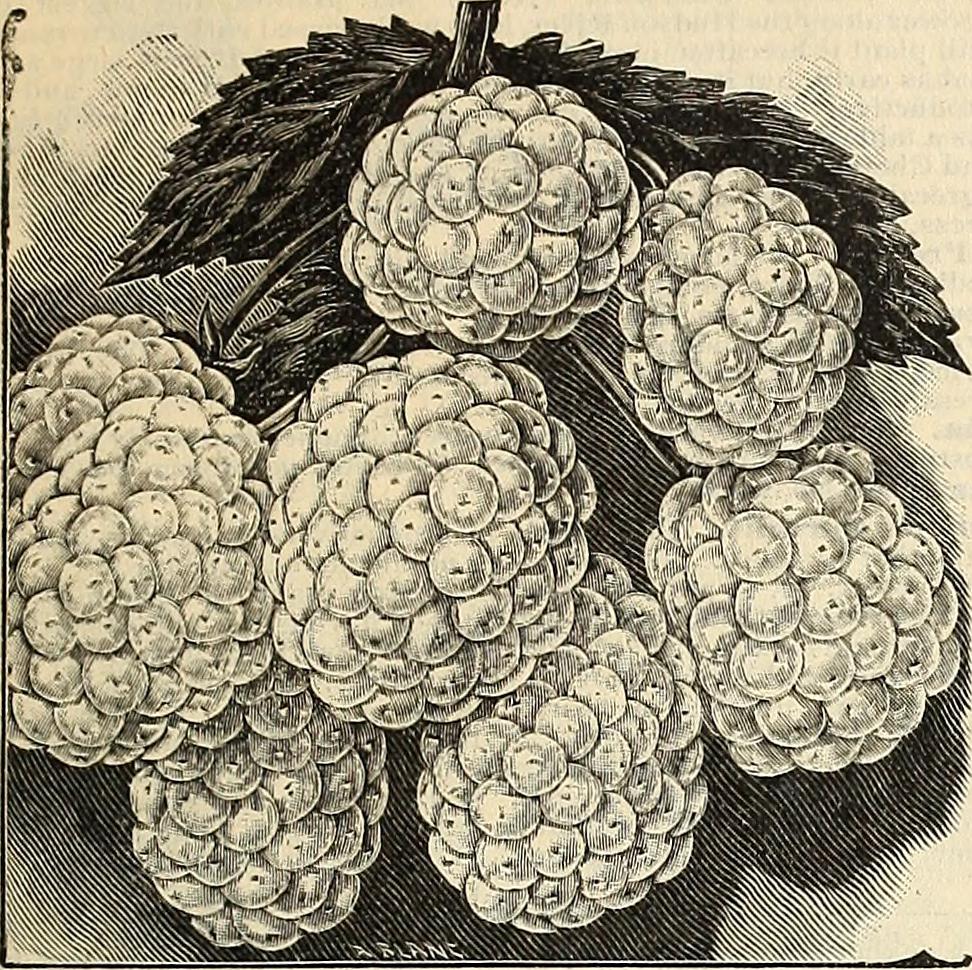

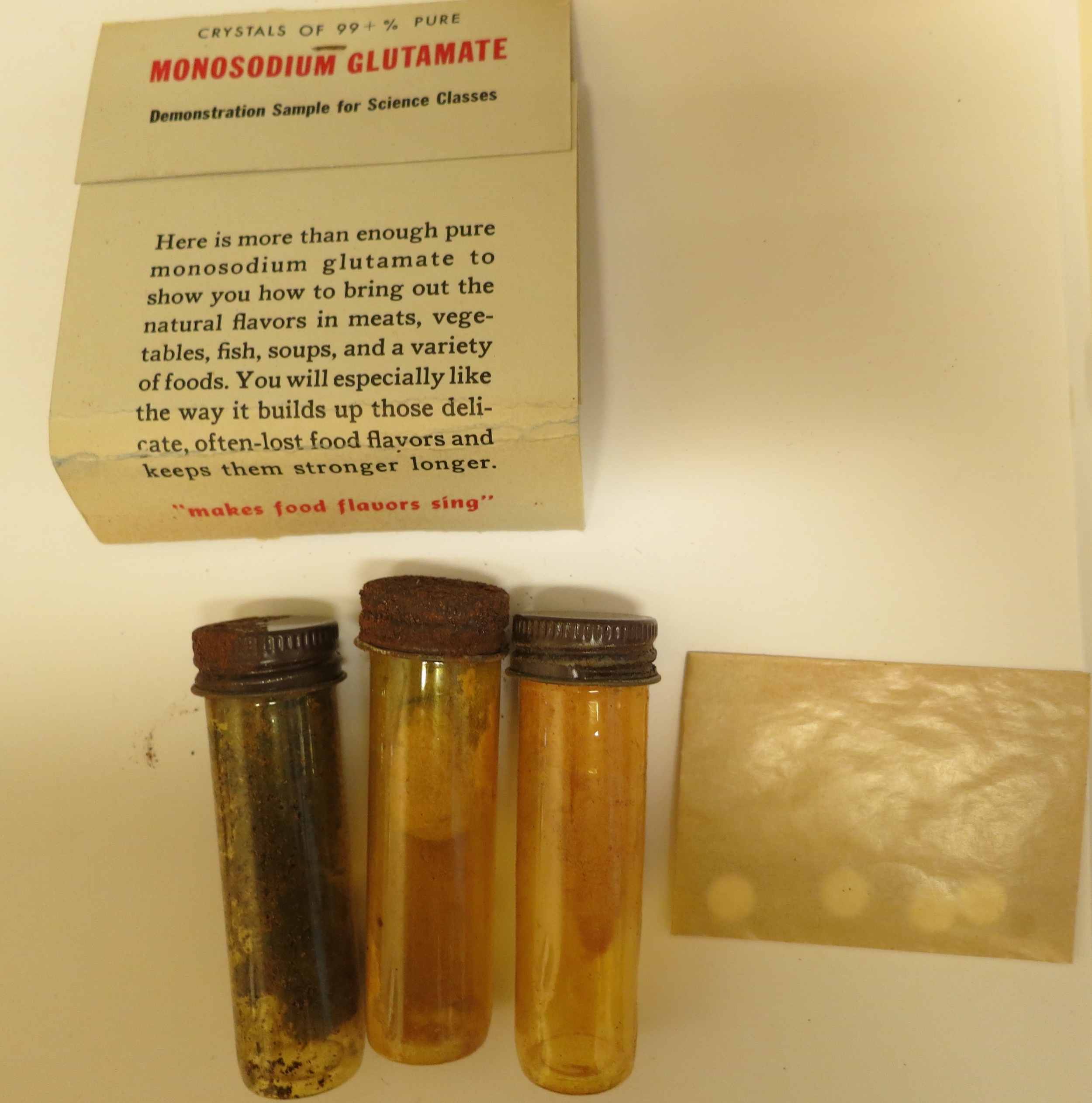

Elsewhere, in an adjacent building, some of these essences were further disintegrated into molecules, or reconfigured into new substances of value. Pure menthol was isolated from peppermint oil; thymol from ajowan seed oil; eugenol from clove oil. These were sold as basic chemicals, or were starting points for further synthetic processes such as the production of vanillin from eugenol, or lilac-scented terpineol from turpentine. Geraniol, a chemical component of rose oil, was synthesized from Citronella oil under a Schimmel-patented process, and combined with true rose oil, to produce an "artificial" rose oil (sold as Rose-Geraniol), which gave the sensory effects of the genuine product for a lower price. In this way, the natural and synthetic were intertwined in the molecular realm.

There was also a dedicated research building, where chemists toiled in “seven large, light and airy work rooms, each for two or three chemists.” This building is where the library was originally located, stocked with several thousand volumes, including chemical journals and dissertations, an international collection of pharmacopeias, and botanical encyclopedias. Other kinds of reference materials were also available: botanical specimens, chemical samples, and “many objects of ethnological interest.”

Research laboratory, site of the original Schimmel Library. From Schimmel & Co.'s Works, 1908.

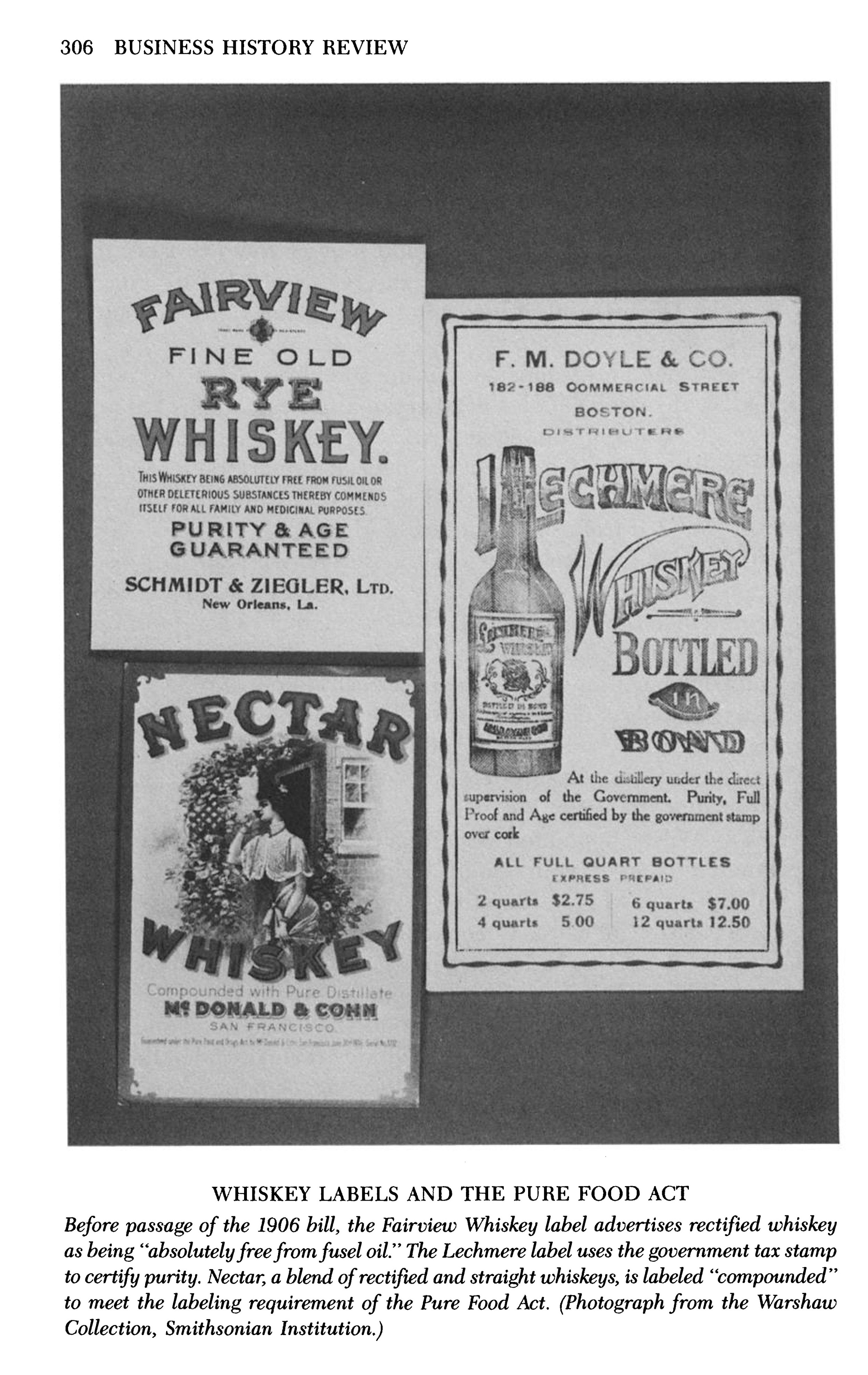

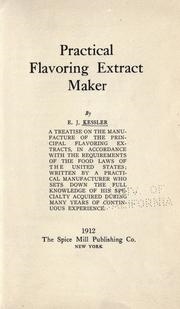

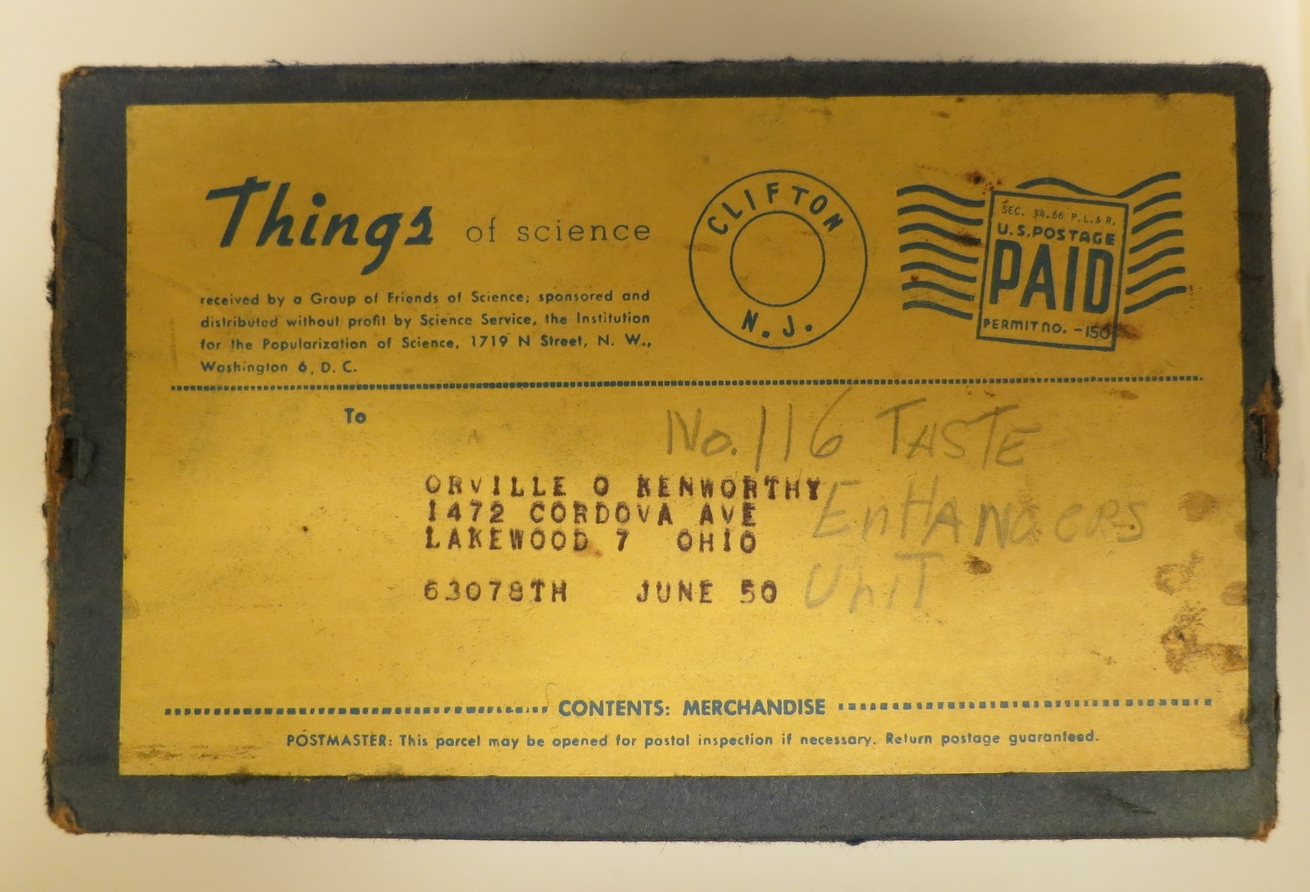

In the research building, chemists analyzed essential oils, identifying chemical components and establishing physical constants, standards of identity, and methods of detecting adulteration. They also worked out ways of manufacturing valuable chemical compounds synthetically. Methyl anthranilate, the chemical used in artificial grape flavor in the U.S., was first identified at Schimmel in neroli (orange blossom) oil, and first produced synthetically there. Chemical analysis was a service that Schimmel & Co. offered, for free, to any clients or potential clients. Send in a sample of a lavender oil or aromatic chemical that a merchant was trying to interest you in, and Schimmel chemists would evaluate it, gratis: exposing adulteration, low-quality materials, or misleadingly labeled goods.

The printing presses in a moment of serenity. From Schimmel & Co.'s Works, 1908.

At Schimmel, the production and distribution of scientific knowledge was intrinsically connected with the production of essential oils and aromatic chemicals. In addition to price lists and catalogs, beginning in 1886, the company published the Schimmel Semi-Annual Report, which compiled the latest scientific, technical, and market news from around the world relating to aromatic chemicals and essential oils. These reports were not just advertising Schimmel’s expertise, they were instrumental in the invention of essential oil chemistry as a scientific field – designating its scope, detailing its methods, and certifying its standards. Nearly 20,000 copies of each issue of the Semi-Annual Reports were printed, in German, French, and English language editions. These and other printing needs kept the four “modern high-speed printing presses” in the company print shop in frequent use, “fill[ing] the air with the hum of restless energy.”

The Schimmel complex in Miltitz was more than a manufacturing and research facility; it was a community, a model social organism. The company provided its employees with on-site health care, opportunities for healthy recreation, and subsidized housing.

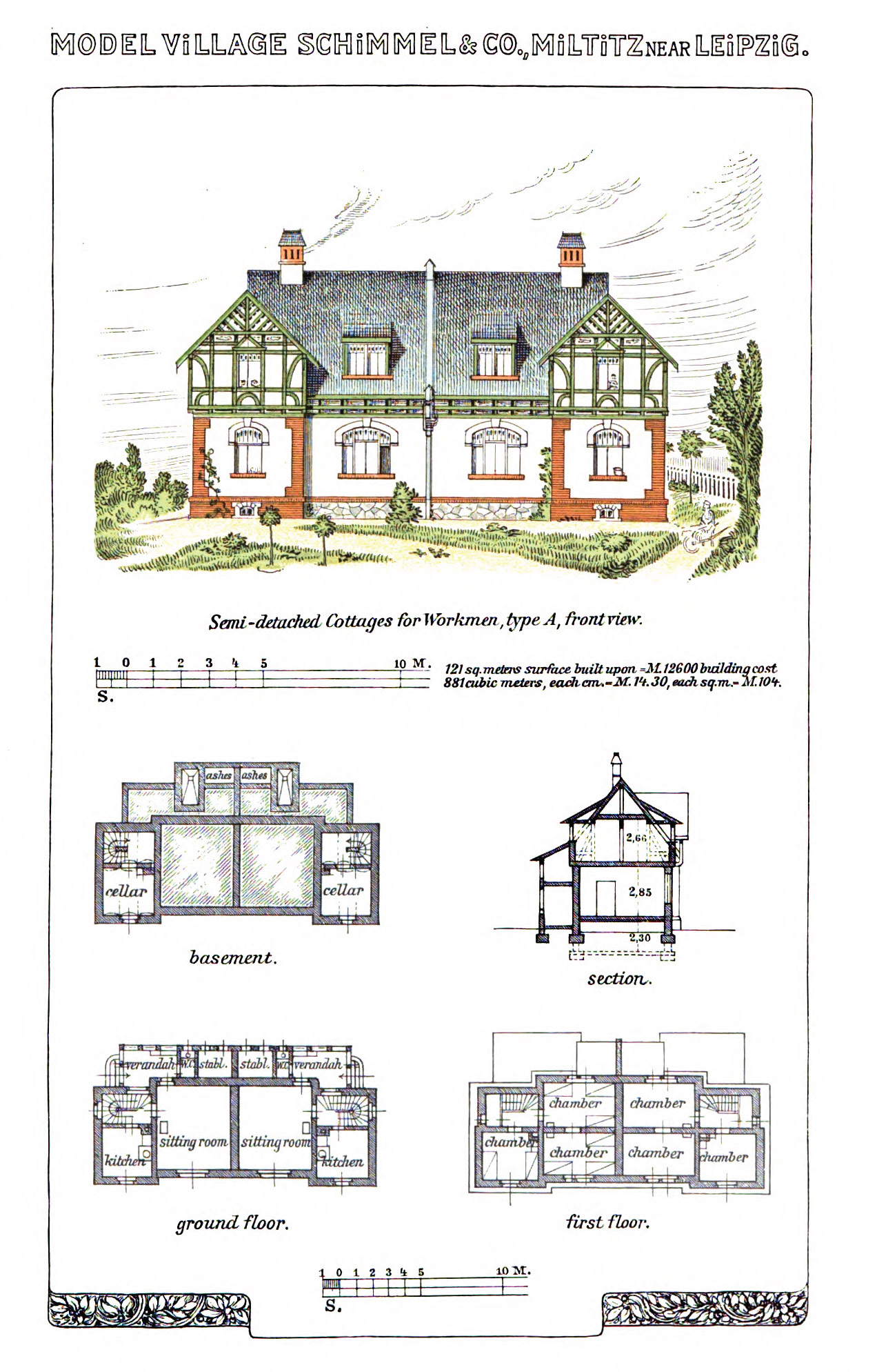

Semi-detached cottages for workmen. From Schimmel & Co's Works, 1908.

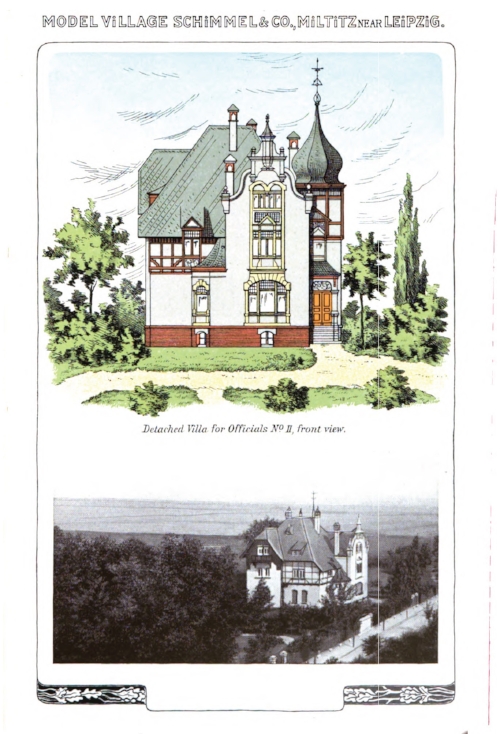

Detached villa for officials. From Schimmel & Co's Works, 1908.

Across from the factory was the “model village,” homes available to Schimmel employees at below-market rent. (For workmen, annual rent amounted to about ten weeks’ pay.) The residences were scaled in accordance with the status of the inhabitants. Families of ordinary workmen lived in semi-detached cottages. Company officials lived in grander, detached villas, with ornate architectural features. Every residence had a large garden, “sufficiently large to provide the families fully with vegetables and fruit.” Additionally, “everyone has the option of a piece of land of about 2000 sq. feet, free of charge, for growing potatoes, cucumbers, beans, etc.”

I don’t know enough about the Fritzsche family, or about German industry and labor politics in the late nineteenth century, to feel entirely confident speculating about the motives behind this corporate paternalism. But part of it was likely the need for securing a stable, skilled workforce outside of a city. Evidently, it was also an effort to correct insalubrious personal habits, and encourage sober and responsible family life by offering positive incentives and opportunities. “At 8 AM the men are given coffee and milk gratis,” according to one of the accounts of worklife at Miltitz, “on the condition that they drink no spirits during working hours.” Workmen could return home for lunch, and enjoy a warm meal with their families, strengthening those bonds of affection. The bucolic location also removed workers from the dissolute temptations of city life. “Instead of spending a considerable portion of their leisure time in the public house, as is otherwise only too often the case, the men are here for nine months out of the twelve occupied in their gardens in the midst of their families.” The houses, the gardens, the annual holiday bonuses, were part of a social project to produce better workers and more virtuous citizens.

Schimmel & Co. was not typical; it was exemplary — and it meant to be. The company deliberately represented itself as a standard-bearer not only for the essential oil industry, but also for the progressive force of chemical knowledge upon the historical trajectory of mankind. What better symbol of the benefits of “progressive chemistry” (as it was sometimes called) than the scientific flavor and fragrance industry, which promised not only to expose false and fraudulent substances — to guarantee authenticity and purity — but also to multiply, by technical means, pleasure-giving molecules? As the world hurtled toward the cataclysm of war, the Schimmel & Co. factory complex and its model village projected a fantasy where all human needs were met, where the rewards of progress were fairly distributed.

The homes still stand today, across the cobblestone street from the factory. (Amazingly, the taxi driver who drove me on the first day of my visit lived in one of them.)

Schimmel Worker's Village, 2017.

And the original brick factories, laboratories, and warehouses are still standing, largely intact, though shuttered and silent.

Chemical manufacturing building on the right. The main essential oil manufacturing building is the large one further back. I think the structure between them was a smaller auxiliary distillation building, where much of the herbs and flowers grown in Miltitz (including roses, hyssop, wormwood, and lovage) were distilled.

Main factory building on the left. The building on the right was one of the boiler-stack buildings. The smokestack was demolished in the early 1990s, after Bell bought the property.

How it looked in 1913. From "A Visit to the Works of Schimmel & Co., Miltitz, Near Leipzig," from American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review, May 1913.

Bell’s current offices, the library, and manufacturing buildings stand where rose fields once spread. (I was not permitted to photograph them.) Much of the land immediately west of Miltitz remains agricultural. A resident of the town told me that they grow corn, wheat, and strawberries.

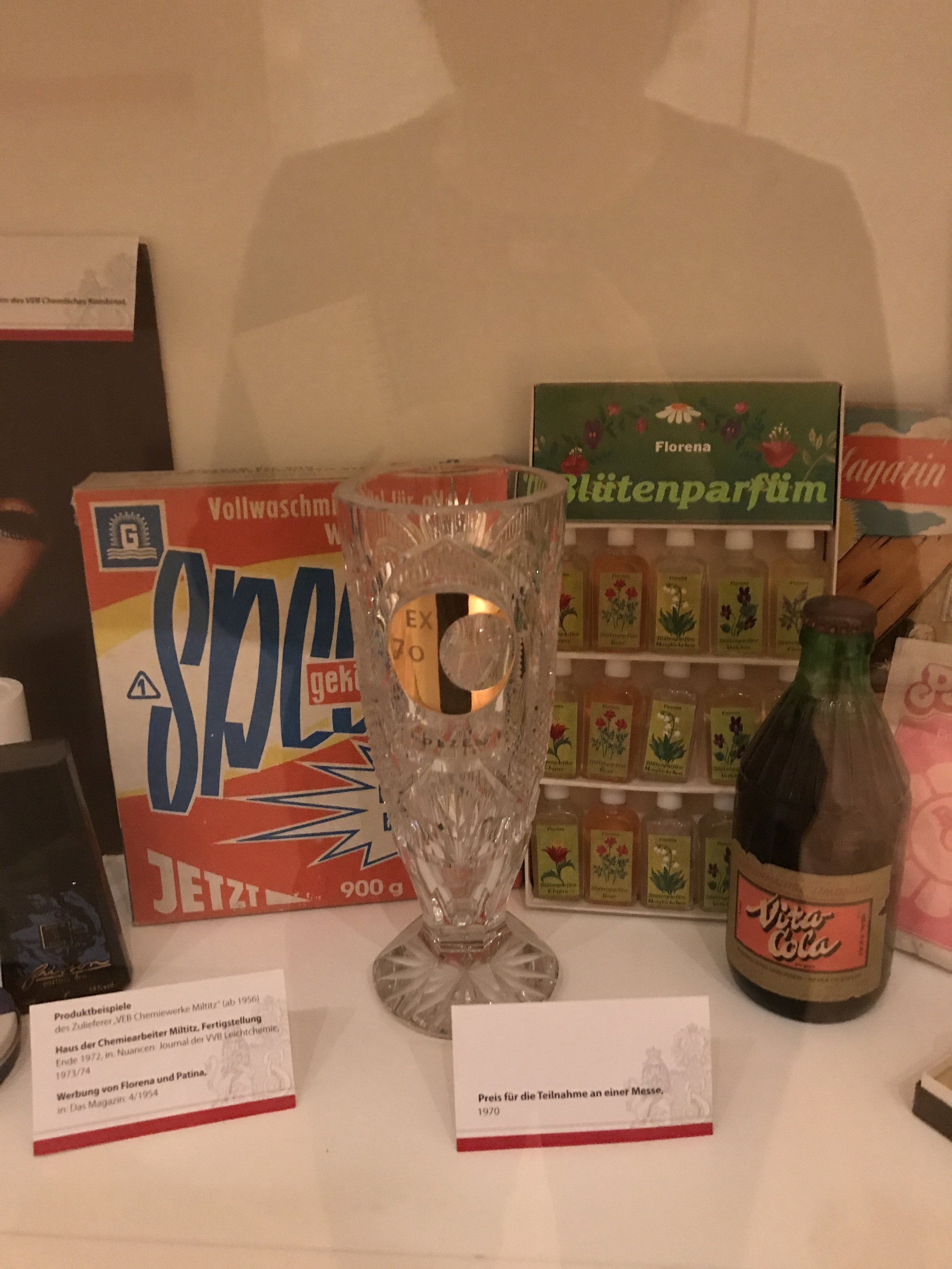

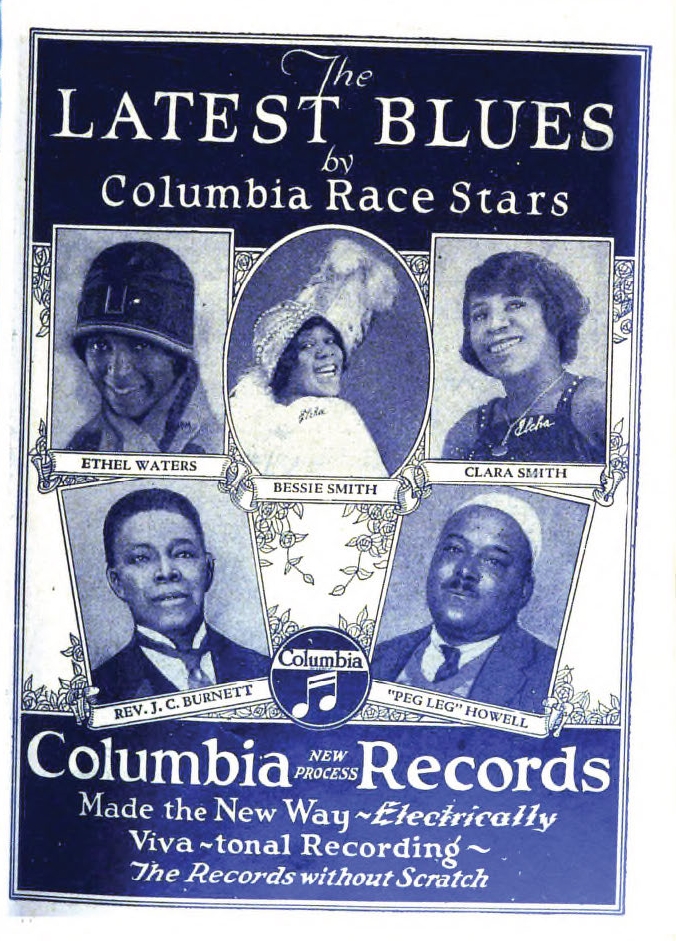

I hadn’t anticipated that the material in the Schimmel Library would thin after 1948, when the company was nationalized under the East German regime. Once a hub in the global exchange of fragrant substances and chemical knowledge, Cold War geopolitics sealed Schimmel off from many of its business and scientific colleagues. The publication of the Schimmel Annual Reports, which had become irregular during National Socialism and the Second World War, ceased completely. At a time when American flavor and fragrance companies were rapidly expanding their research and development operations, the Schimmel Library in Miltitz was stunted by politics. The factory continued to operate, supplying the eastern bloc and Soviet client states with : orange flavor for Cuban toothpaste, cheap floral perfumes for East German ladies, as well as the flavor for Vita Cola.

Some of stuff containing Schimmel & Co.'s flavors and fragrances produced in the DDR.

Vita Cola was the DDR’s answer to the Coca-Cola and its smooth inducements to global capitalist hegemony. I’d like to buy the world a Coke… Vita Cola gave East Germans an alternative way to quell their thirst and their desires for refreshment. Originally imagined as a caffeinated lemonade, Vita Cola provided liquid pep to sustain industrial toil and lift sluggish spirits. It had a distinctive citric tang, and was less sweet, than its Western rival.

Vita Cola advertisement in Hungarian that I found on Pinterest. Wish I had more info on this...

Apparently, Vita Cola is having a moment right now, at least around Leipzig. It is the number one cola beverage in Thuringia, making the region one of the only places in the world to favor a local cola over Coke's global hegemon. The craving for Vita Cola is generally related to what's been called "Ostalgia," a nostalgic longing for the symbols and quotidian artifacts of life in East Germany -- a phenomenon that points to kitsch's emollient power to soften and heal, but also perhaps to the wish that another kind of world were (still) possible. (It is.)

The production of Vita Cola was suspended after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, but it reappeared in the early 1990s. Its essence is still made in Miltitz, though now under the auspices of Bell Flavors and Fragrances (the lollipop scent in the air?)

A bottle of Vita Cola stood waiting for me when I visited the Schimmel library, effervescent with the past and with the welcome chemical boosters of sugar and caffeine.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC LINKS:

A 1908 English-language booklet that offers a virtual tour of the Schimmel Works at Miltitz from the University of Wisconsin Madison library is digitized, searchable, and fully viewable at Hathi Trust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007453174

You can also find many copies of the Schimmel Semi-Annual report on the site: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000675259

The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review published a similar (but not identical) account of the Schimmel works at Miltitz in its May 1913 issue, but it was an unpaginated insert, and doesn't seem to be included in digitized copies of that publication available online.

Essential oil nerds may want to check out Gildemeister and Hoffmann's Volatile Oils (or the find the original, in German, if you can read it). The English edition was translated in the early 20th century by Edward Kremers, a professor of pharmacy at University of Michigan, a character who appears often in the debates around pure food and flavor additives, but who I don't know that much about. Volume I of Volatile Oils is entirely historical -- it includes a history of the spice trade, of particular oils and scents, and of methods and technologies for producing essential oils. Here's a link to Volatile Oils: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001036302

"Here's how you can see how superior socialist consumerism can outmatch capitalist production." For those of you who want a place to start on your Vita Cola internet rabbithole.