Sexy celery beckons you, with chemistry. Illustration by yours truly.

Earlier this month, NPR's excellent blog The Salt posted an article entitled, "Celery: Why?" In it, science writer Natalie Jacewicz ponders what she calls the "paradox" of celery. Despite minimal caloric value and, in her words, "about as much flavor as a desk lamp," celery has featured in Mediterranean and East Asian cuisines for thousands of years. Why even bother? How did this apparently useless vegetable "sneak into our diets?"

She talks to a series of ethnobotanists, plant geneticists, and other celery experts, who dilate on the plant's traditional medicinal and fibrous virtues (the highlight is a spokesperson for the Michigan Celery Promotion Cooperative who describes it as the "classic rock" of vegetables). Throughout, I remained dumbfounded by the very premise of the article. Was she even talking about the same celery that I know as celery? To me, celery is intensely, distinctly, undeniably aromatic and flavorful. Its fragrant leaves add a musky green complexity to unctuous and savory things; its crisp and slightly bitter stalks perfectly counterbalance the heat of szechuan peppercorn and the slick fat of stir fries; its pungent seeds are super excellent in potato salad and pickle brines. Its appeal is obvious.

I'm pretty sure that we're both eating more or less the same celery, and I don't doubt that Jacewicz finds celery flavorless, just as I don't doubt my own experiences with the vegetable. But our vastly divergent responses point to a problem that has haunted the various philosophic and scientific disciplines concerned with studying flavor phenomena since the beginning. How do you produce reliable, reproducible, scientific knowledge about the sensory qualities of foods when tasters are liable to have incommensurable responses to the flavor of the same thing? Or to put it another way, is a difference in taste a difference in personal opinion, shaped over the course of one's life history within given social and cultural contexts, or does it signal a physiological difference in bodily systems of sensation and perception?

This implies it's either one or the other, when of course, reality is much much messier. It's always both, and can never be neatly sorted into "biological/natural" and "social" sets of causes. In this case, however, the idea of flavorless celery was so bizarre to me, that I wondered whether its flavor was associated with any chemical substances that are known to have different sensory effects for different people. I've written about PTC here before, and most people know that the flavor of cilantro is controversial; depending on your chemosensory affordances, it's green and heavenly or soapy and weird. Could different responses to celery likewise be an index to genetic differences among the population at large?

I tweeted out a question along those lines, and a one-word reply soon arrived from the Monell Chemical Senses Center: Androstenone.

After I posted this blog with the picture of Ms. Sexy Celery above, I realized that the purported heterosexual dynamics of androstenone were much better illustrated by a celery that was sexily gendered male. I'll leave unexamined here the admission that even a self-declared feminist (yours truly) reflexively defaults to the feminine when depicting sexiness. Masculine sexy celery, also beckoning you with chemistry (powerfully?), is my attempt to remedy the earlier mistake.

[P.S. My Twitter handle is @thebirdisgone, if you wanna follow me. This whole celery-flavor-rabbit-hole that I fell into was largely dug on Twitter, with the able assistance of Paul Adams (@PopSciEats), John Coupland (@JohnNCoupland), Susie Bautista (@flavorscientist), and Monell (@MonellSc), among others.]

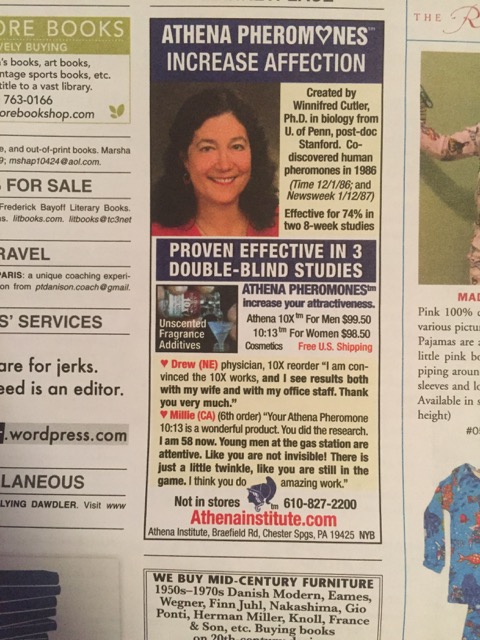

An internet search quickly uncovered that androstenone was the first mammalian pheromone to be identified. Pheromones are understood to be biochemical signals emitted by animals, and producing behavioral, social, or physiological responses in other members of the same species. According to Wikipedia, in addition to "celery cytoplasm," androstenone has been found in the sweat and urine of both male and female humans, and in the saliva of male pigs. When inhaled by a female pig in heat, the odor of androstenone triggers her "standing reflex," a pose of sexual receptivity. For this reason, synthetic androstenone is the active component of DuPont's "Boarmate," a spray used to get sows in the mood, in order to facilitate artificial insemination. Possibly for this reason (if you can call it one), androstenone is also a component of the various pheromone perfume potions that you sometimes see advertised in the back pages of high-class magazines like the New York Review of Books and Harper's — even though the readers who encounter these inducements are likely not porcine. The supposition here is that somehow androstenone "means" a similar or analogous thing among humans that it does in pig-world; suffice it to say, the evidence for even a slight correlation between the chemical and attraction and arousal in humans is thin and disputed, and it undisputedly does not produce similar behavioral effects (it should go without saying!) [Edit: after I posted this, Monell tweeted to say that there is no good evidence that androstenone is a human pheromone.]

"I see results both with my wife and with my office staff." Um, creepy? This is from the July 14, 2016 New York Review of Books.

The androstenone-arousal "connection" is also why celery takes the top spot in this listicle of "Foods that Make Men More Sexually Attractive." According to Alan Hirsch, M.D. (author of Scentsational Sex), androstenone and other related hormones released from celery when you chew it travel into your olfactory cavity, "turning you on, and causing your body to send off scents and signals that make you more desirable to women." ("Men, you could do worse than ordering a Bloody Mary at brunch," the article advises.)

Sometimes traces of androstenone remain in the meat of uncastrated pigs, leading to an off-flavor in bacon and chops that goes by the evocative name "boar taint." The chemical also contributes to the odor of truffles.

There is also strong evidence that people perceive androstenone differently. To some people, its smell is reminiscent of vanilla and sandalwood. To others, it stinks like rancid piss. These differences in reported perceptions have been correlated with specific genetic differences. However, perceptual differences do not necessarily correspond to preferences, which are shaped by social and cultural factors as well as circumstantial factors, such as familiarity. Cilantro may taste like soap to you, but even so, you might like it; you might even be able to learn to like it. Finally, there's a portion of the population that cannot perceive androstenone at all — people who are, technically speaking, anosmic to it.

I confess that I'm attracted to (or at least not generally repelled by) musky, fetid, all-too-human smells. Sweaty bodies on the subway in the summertime, unwashed hair, steamy yoga studios, dirty T-shirts pulled from the laundry hamper -- none of these things really bother me, and I'll admit there's a certain interest factor when the world's ripe and rankness makes its presence known despite all our attempts to mask and tame its pungencies. Napoleon's loving plea to Josephine, "I'll be home in three days. Don't bathe," totally makes sense to me.

So am I a celery lover because I'm chemoreceptive to androstenone, and generally into a little funk besides? (I should probably note here that I do not think boars are sexy.) Does Natalie Jacewicz think celery has the flavor of a desk lamp because she's (possibly) anosmic to androstenone?

In other words, can our different responses to celery be partially accounted for by our different chemosensory receptivities? Not so fast.

"Wysocki just now noted no citation for andros/celery claim," tweeted Monell. Charles Wysocki and Gary Beauchamp are two scientists at Monell who, in the 1980s and 1990s, did foundational work on androstenone perception in humans. Wysocki had gone back to one of his articles on the subject, and found that the claim (more of an aside, really) that androstenone is found in celery had no reference to back it up.

It turns out that the vast majority of scientific studies concerning androstenone don't have anything at all to do with celery. They're interested in androstenone's role as a chemical messenger, namely, the ability of androstenone released by one individual to influence the disposition and behavior of other individuals (whether boar or lab-mouse or human). Scientists have studied, for instance, the olfactory and sensory mechanics involved in androstenone perception, the psychological and behavioral effects of the chemical, and the genes associated with different reactions to it. In many of these papers, celery plays a kind of wacky walk-on role at the very beginning, a humble escort to high-class truffles — just incidental examples of the other company this promiscuous pheromone keeps. Very, very few papers cite any source for the claim.

Even when celery does make a more than incidental appearance, its link to androstenone is usually not elucidated. For instance, a 1998 study investigating whether the "scent of symmetrical men" was more appealing to ovulating women asked the men to refrain from eating a number of foods, including celery, for the duration of the experiment. I'm presuming that the prohibition on celery was to ensure that the men's "natural" androstenone levels were not elevated through vegetable means, though the study's authors do not explain the forbidden celery, nor any of the other food restrictions (a long list, which also included garlic, lamb, yogurt, and pepperoni).

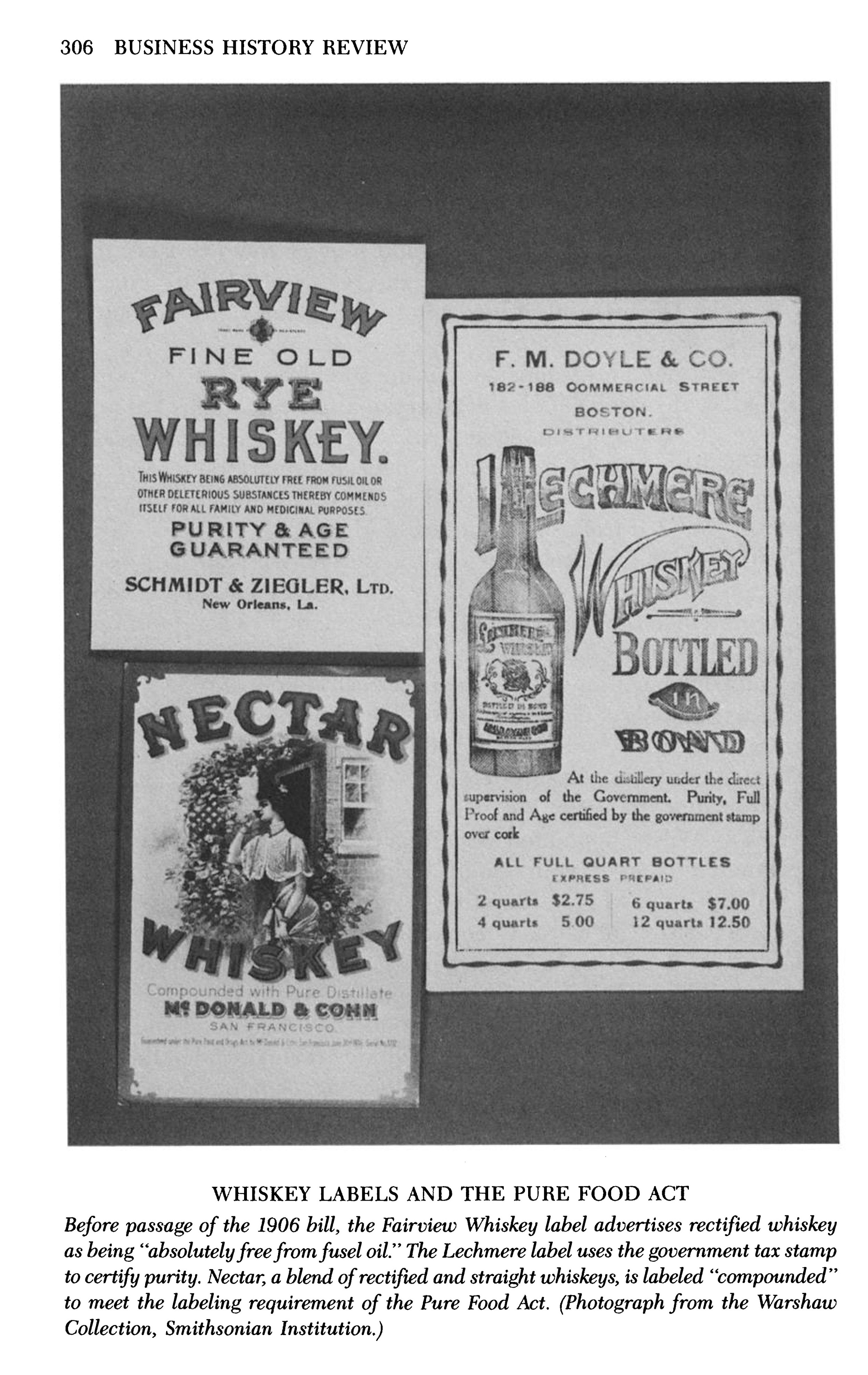

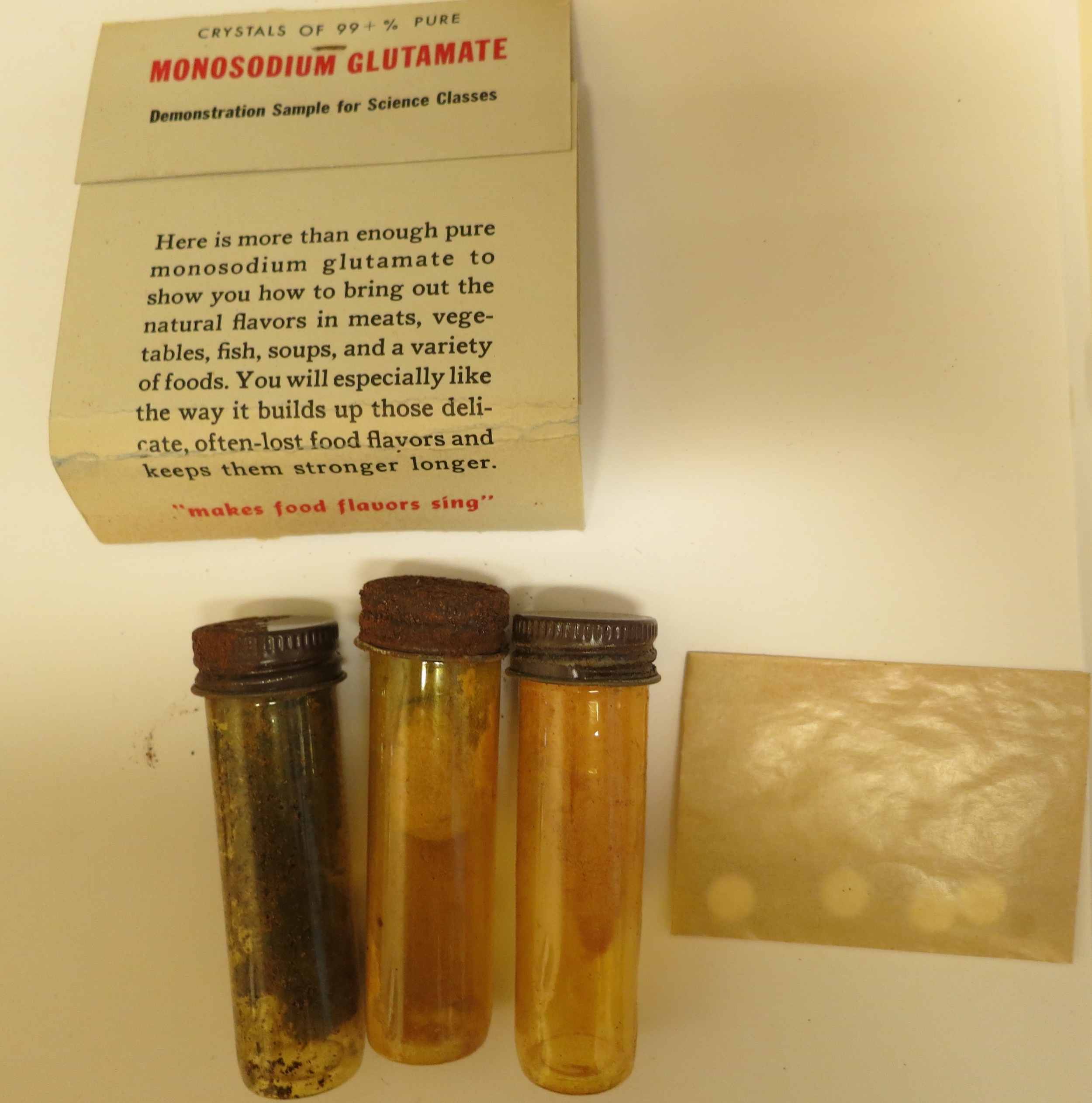

It turns out that the claim that androstenone is present in celery can be traced back to one wisp of an article from 1979. Paul Adams at Popular Science unearthed a copy from a digital archive of the Swiss life sciences journal Experientia: "The Boar-Pheromone Steroid Identified in Vegetables," by Rolf Claus and Hans-Otto Hoppen, two biochemists at the Technical University in Munich who worked on boar endocrinology.

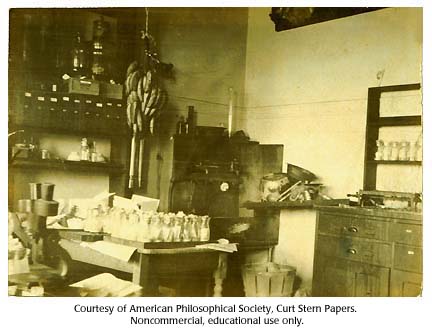

"The initial impetus for these investigations was provided by the wife of one of the authors," the article explains. "She was familiar, from her husband's work, with the characteristic smell of boar taint, and noticed this smell when cooking parsnips grown in her garden." The wife's name is not given, so we'll never know which of these two guys regularly returned home smelling like boar taint. But her sensory observation was looked into, and Claus and Hoppen tested parsnip extract for the pheromone in the biochemical lab.

And she was right! It was only after finding androstenone in parsnips did they test other vegetables: carrots, potatoes, radishes, fennel, salsify, parsley, and celery. Of that vegetal bounty, celery alone was found to contain androstenone.

Both celery and parsnip had "remarkably high" concentrations of androstenone, between seven and nine nanograms per gram. "For comparison," the authors explain, "concentrations in peripheral blood plasma of mature boars... are in the same range." Suprising, but not unprecedented, as they note that other plants are known to contain compounds that mimic or duplicate animal hormones — phytoestrogens, for instance. But the biological purpose (if any) of androstenone in celery remained unaccounted for, and "neither is it known if the boar taint substance in celery contributes to the 'libido-supporting' property for which this plant has some popularity."

Shortly after this study, Claus and Hoppen were involved in research that detected the presence of androstenone in prized Perigord black truffles. The New York Times and other media outlets wrote about new scientific discovery of the pheremonal appeal of these super-luxurious super-delicacies. In an aside, some of these articles note that the chemical is found in parsnips and celery, too — a way, perhaps, for the rest of us supermarket shoppers to get in on the sexy-boar fun of rich people food. Possibly this was the first step toward this very thin fact assuming the ripeness of common knowledge, blooming without attribution over the fields of popular media and scientific literature.

I can't find any other record of these experiments being repeated, or these results confirmed. (Which doesn't mean that it isn't out there, or that it hasn't been done.) I don't mean to cast doubt on Claus and Hoppen's results, which seem careful and reliable and involve both radioimmunoassay and GC-MS analysis, nor do I mean to dispute whether androstenone is "really" present in celery. But generally we do like to think that common knowledge (and especially scientific common knowledge) is built on sturdier foundations than a single decades-old study.

This happens all the time, though. A claim gathers credibility and authority as it is repeated and republished, an effect that is amplified by the perceived prestige of the source. Some examples: Spinach did not make Popeye strong because of its iron content. (Read this fascinating essay about "academic urban myths" to find out more about that one.) Our bodies are probably not 90 percent microbes -- that one is actually based on a single 1972 study that extrapolated from a fecal sample. The oft-repeated claim that one in three women over 35 will be unable to get pregnant is based on French birth records between 1670 and 1830, hardly a sample reflective of current biomedical and social circumstances. Napoleon probably never said that thing about not bathing.

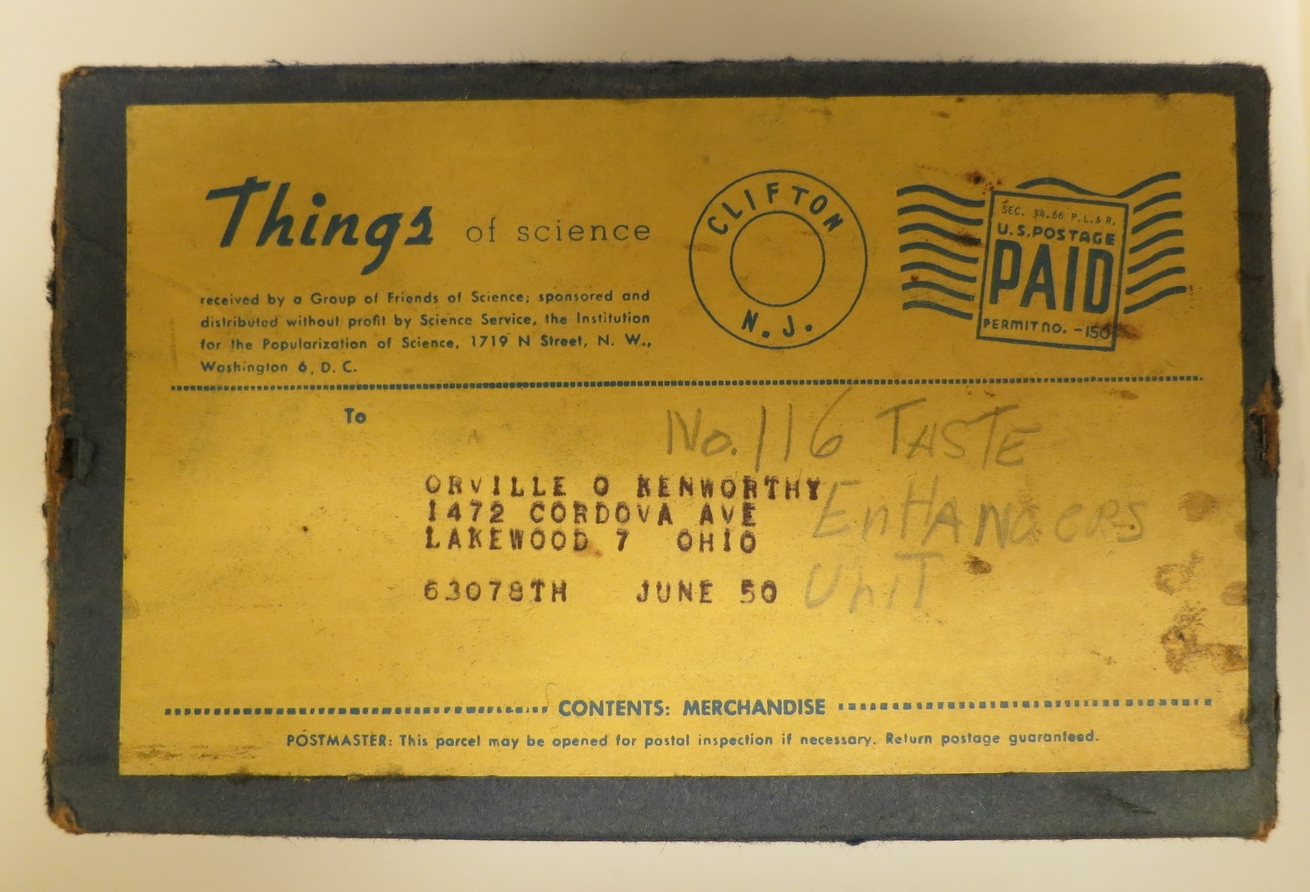

We often take for granted or leave unconsidered the basic facts about what comes to count as facts. I'm working on a dissertation chapter now about what the introduction of megapowerful analytical instruments, gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, meant for the work of flavor chemists and flavorists. What's striking is how intertwined sensory and instrumental analysis remain. The standard story we're told about the history of science in general goes something like this: people used to rely on imprecise and unreliable sensory knowledge. An alchemist smelled and tasted a solution, in order to say what it was. Then we built objective instruments that could get at some underlying, universal reality about things, despite ourselves. A chemist measured and quantified, to identify a substance. Thus, the astute sensory observation of the scientist's gardening wife — parsnips smell like boar taint! — becomes scientific knowledge only when confirmed instrumentally in the laboratory.

But the data produced by powerful "objective" analytic instruments like the GC-MS have to be repeatedly confirmed by "nasal appraisals," at multiple stages through the process. "Without sensory evaluation chemists have no guideposts and will almost certainly lose their way among the byways of flavor research," instructs the 1971 textbook, Flavor Research: Principles and Techniques, a book that is almost entirely devoted to explaining the use and operation of a battery of complex lab instruments, but which nonetheless proclaims "the human nose" to be "the ultimate instrument in flavor chemistry." Rather than replacing the "unreliable" evidence of the senses with information untainted by the subjectivity of the human body, the reliability of these machines must be vouchsafed by the senses. And even so...

On the one hand, we think of sensory experiences as a sort of personal knowledge. Each of us knows what we taste — perhaps we can learn to taste more acutely, more articulately, but our certainty will be our own. Celery is this for me, for you it may be quite different.

But the "pheromonal" flavor of celery also provides an example of another way that we tend to think about flavor and its effects. Flavor chemicals are members of a world of influential chemicals, which act on us in ways that we cannot detect and thus cannot reasonably resist, and which perhaps induce us to take actions that are counter to our better interests. This way of thinking about flavor slips into the impersonal, the universal. Thus, the seeming ease of making the leap from the effects of a chemical in pig saliva on other pigs in particular physiological circumstances, to the effects of celery on a man's attractiveness to women. (I fall into this fun rhetorical trap too, above, when I wonder whether my olfactory interest in sweaty people is related to my taste for celery.) You also find it in critiques of the food industry, such as Michael Moss's Salt, Sugar, Fat, where flavor is depicted as an addictive force, designed to make us fall for the wrong snack rather than the steady, reliable, "genuine" food.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes' investigation of and meditation on the nature of photographic images, he proposes to understand these artifacts by considering only the ones that have an undeniable personal effect on him. This is how he explains it:

In this (after all) conventional debate between science and subjectivity, I had arrived at this curious notion: why mightn't there be, somehow, a new science for each object? A mathesis singularis (and no longer universalis)?

It's a counter, original, spare, and strange understanding of science, but what if we understood and pursued knowledge about flavor this way, too?

Okay, that's probably as far down as I want to go now into this particular rabbit warren. As a token of forgiveness for all that maundering pseudo-philosophy, I'll leave you with this:

![The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification Set, sold by Cargille Scientific Supply. From Alden P. Armagnac [yes, that is a real name!], "What Is a Stink?" Popular Science, March 1949, p. 147. An amazing article that has some more background…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/520a3a3ee4b04f935eefceef/1408987898623-BT0VAU73A3UVIPNC1BMA/Crocker-Henderson+Odor+Classification+Set)